During a recent literary festival at a nearby college, the usual discussion about finding one’s voice came up. All the familiar suggestions were made: figuring out a preferred medium, discovering whether to write chronologically or in segments, writing what you know versus following the elements of a story (Plato versus Aristotle, as I like to think of it), and so on. When my turn came to speak, I realized I had been giving the same advice for years but never written it down: experiment with writing at different times of day.

The human brain is a trickster god, and its greatest gag is its way of shifting its own perspective as the hours pass between waking and rest. A writer might have different voices during those different hours—a time-voice, say, or time-voices. By working at different times, a writer can figure out whether words come best at dawn or dusk, noon or 2 a.m.

That isn’t to say that any writing time isn’t valid, but that the author might have several different time-voices, as I do. Mastering them can help with creating the true big-V Voice.

Here’s how it works for me:

1) In the morning, my mind is blank. I often have no idea what will come out of my head when I start to write. The ideas come as simple epiphanies and build inside me, spilling out in an almost stream-of-consciousness style. These microbursts are often quite lovely and have their own momentum. As such, I’ve found that, for me, mornings are best spent writing poetry.

2) At night, my head is full. The day has worn on me. My anxieties have flared and exploded so many times that I wonder how I’ve survived. Throughout the day, I’ve observed, feared, been awed, and felt anger, desire, embarrassment, and dread. I’ve contemplated angles. I’ve lived and experienced everything from monotony to chaos. This is every day for me, and as night comes, my thoughts swirl around, waiting to be focused. At nighttime, therefore, I’m better equipped to take on short stories. I have to lasso these images and ideas, then herd them together. At that point, stories grow from the energetic hodgepodge of my thoughts.

3) In the afternoon, it’s easier for me to establish a routine. My head is full enough to know what I want to say, but empty enough that the process of saying it and figuring out what comes next is still interesting to me. The afternoons are often the best time for me to attempt longer works. In the past, these have been my novel-writing hours.

I know these things about myself and have been able to use them effectively in my writing. That’s not to suggest that writing at the same hours will lead to the same results for anyone else. I am saying only that there is value in testing different time-voices. My advice is the same as it would be when determining whether to write with a notebook, laptop, or voice recorder: try them all and figure out what works best for you.

Today we are pleased to feature author Sunny Nestler as our Authors Talk series contributor. The artist takes the time to discuss their recently self-published artist book Undergrowth in which five drawings previously published in SR are featured. They consider the creation of the book with their collaborator, A A Spencer, as they talk about the artistic and creative choices that went into developing it.

Today we are pleased to feature author Sunny Nestler as our Authors Talk series contributor. The artist takes the time to discuss their recently self-published artist book Undergrowth in which five drawings previously published in SR are featured. They consider the creation of the book with their collaborator, A A Spencer, as they talk about the artistic and creative choices that went into developing it. Today we are pleased to feature author Chelsea Dingman as our Authors Talk series contributor. In her podcast, Chelsea discusses her creative process and how it “almost always stems from reading and discussion.” She also reveals that she loves “that poetry lives in uncomfortable, uncertain circumstances…There’s no resolution required in a poem.”

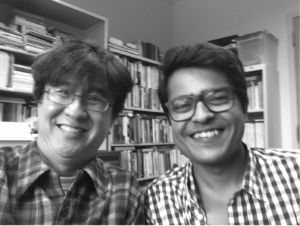

Today we are pleased to feature author Chelsea Dingman as our Authors Talk series contributor. In her podcast, Chelsea discusses her creative process and how it “almost always stems from reading and discussion.” She also reveals that she loves “that poetry lives in uncomfortable, uncertain circumstances…There’s no resolution required in a poem.” Today we are pleased to feature author Timothy Liu as our Authors Talk series contributor. In his podcast, Timothy is interviewed by Karthik Purushothaman, one of his graduate students, about his newest book,

Today we are pleased to feature author Timothy Liu as our Authors Talk series contributor. In his podcast, Timothy is interviewed by Karthik Purushothaman, one of his graduate students, about his newest book,  The pair discusses the book as a hybrid novel, and they explore the way it blends poetry and prose. Timothy also shares his process for this novel and reveals how he completed the first draft in 2008 after writing every day for three months. Karthik then asks Timothy about his inspirations, and Timothy talks about the different books that he kept on his desk while writing and how they influenced the book.

The pair discusses the book as a hybrid novel, and they explore the way it blends poetry and prose. Timothy also shares his process for this novel and reveals how he completed the first draft in 2008 after writing every day for three months. Karthik then asks Timothy about his inspirations, and Timothy talks about the different books that he kept on his desk while writing and how they influenced the book.