Barnhart Studio, a castle of metal and cinderblock, is tucked into a Mesa residential area. When I ring the doorbell, an unassuming man in a t-shirt opens the door: William Barnhart.

Barnhart Studio, a castle of metal and cinderblock, is tucked into a Mesa residential area. When I ring the doorbell, an unassuming man in a t-shirt opens the door: William Barnhart.

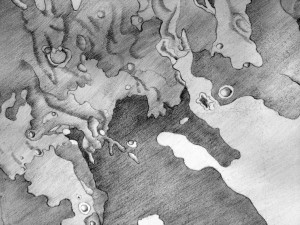

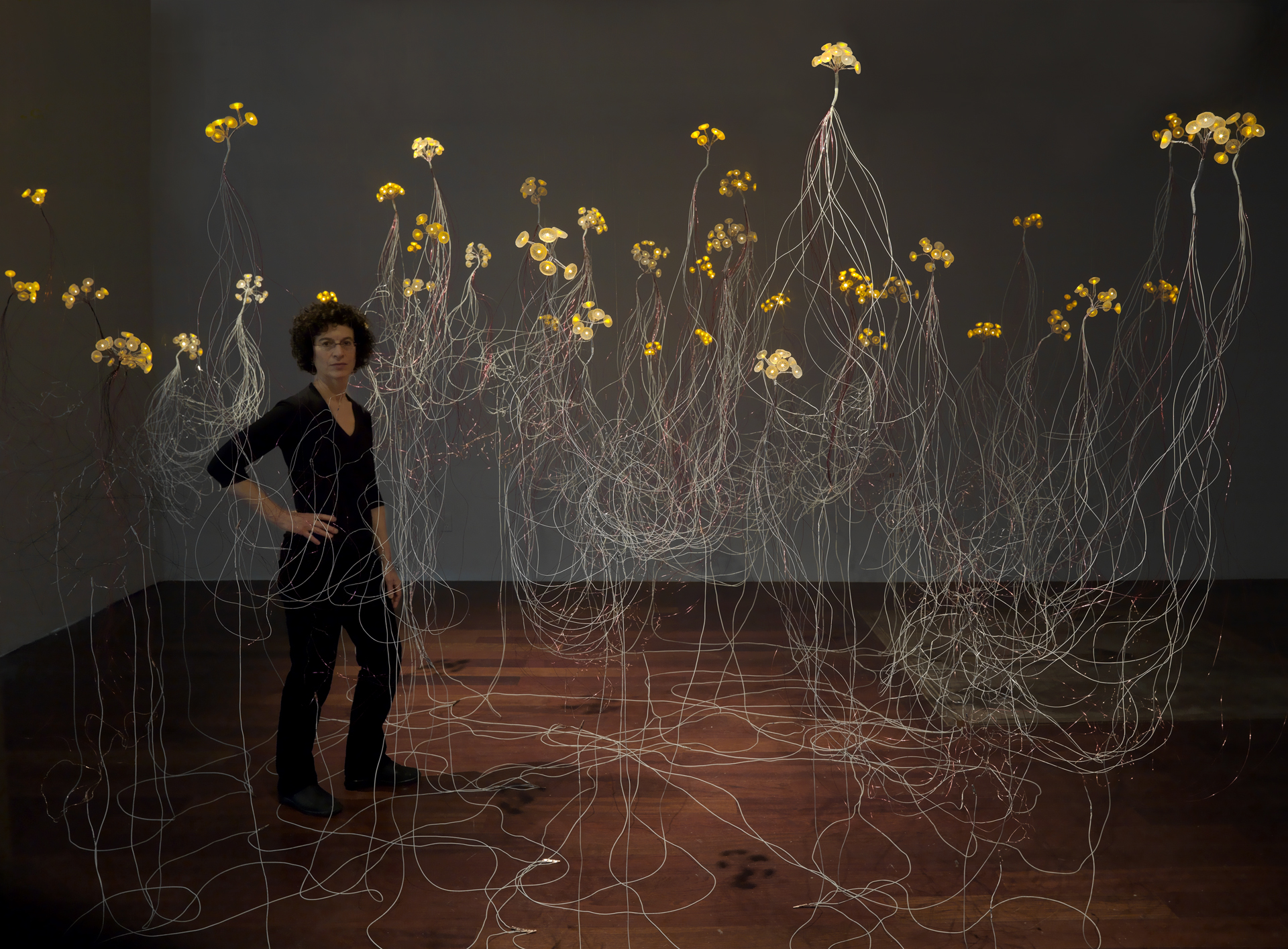

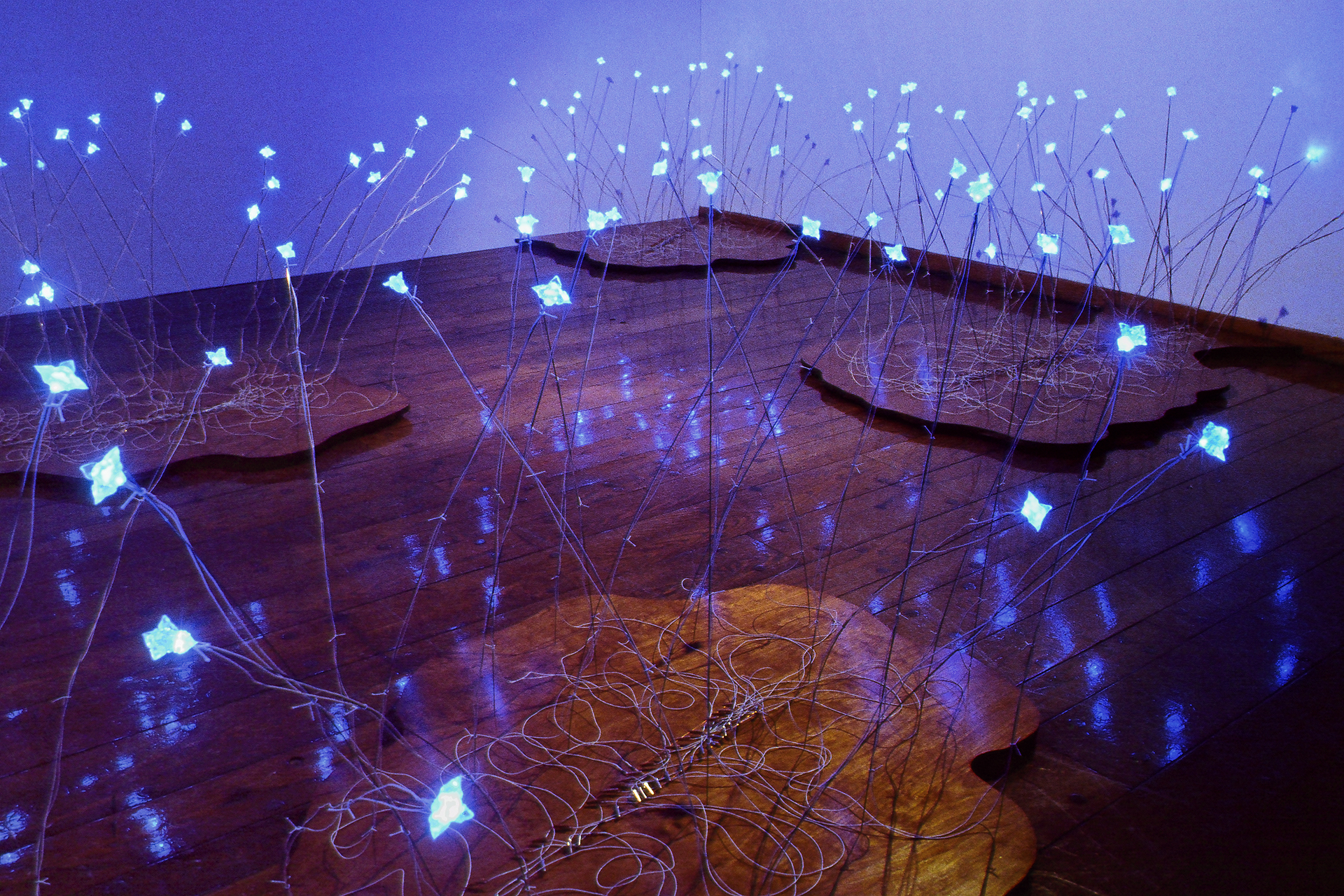

After a brief introduction, I am given a tour of the studio. William starts from the foundation of the building. From the tile work on the bathroom walls to the welding on the doors, most of the fixtures in the building are made from recycled materials, and they are all William Barnhart’s handiwork.

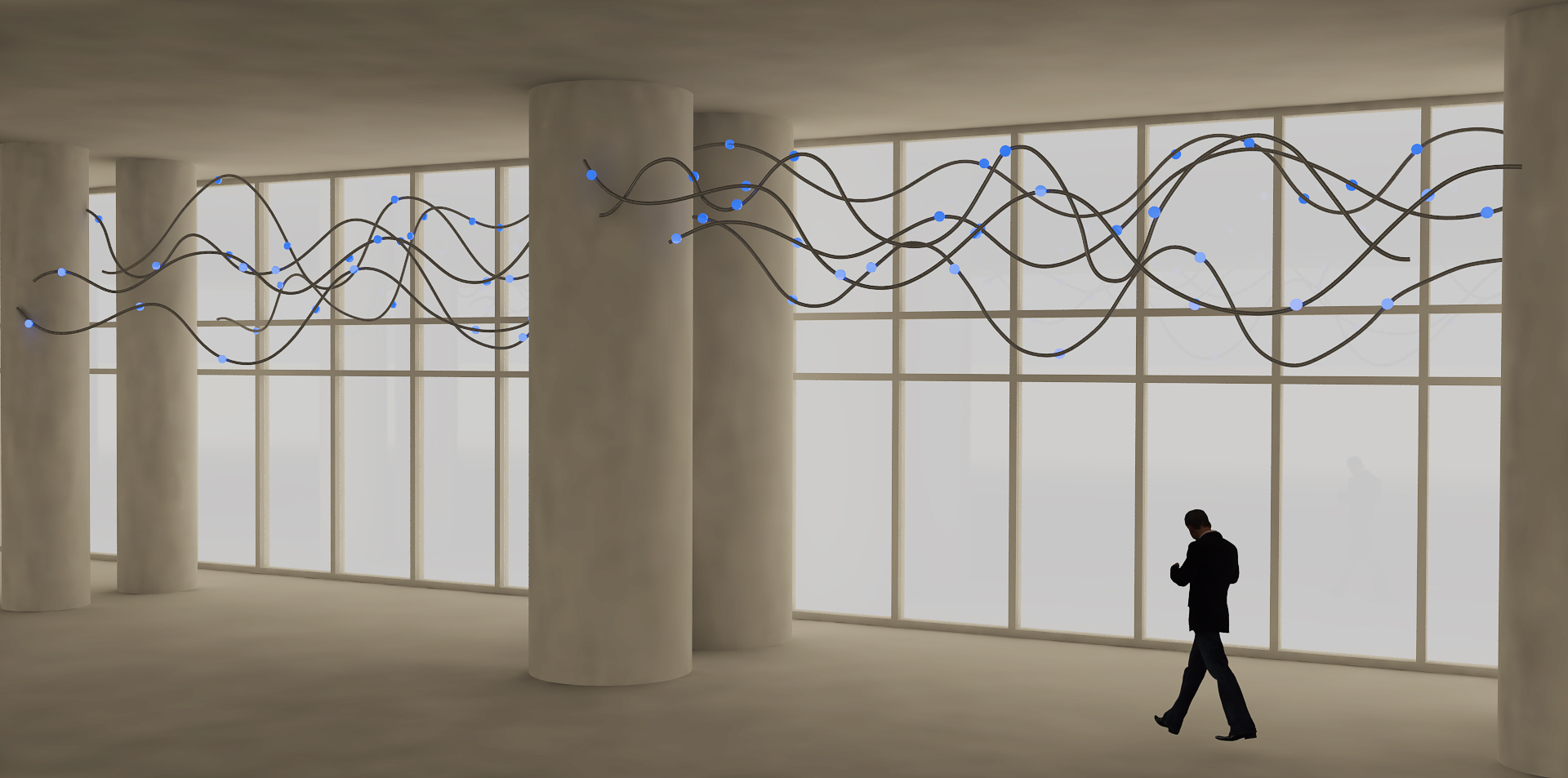

The very studio where William works is a reminder that art sometimes requires more than a table and chisel or paintbrush. The studio resembles a mechanic’s garage, a zone under construction, where a plaster sculpture waits to be completed. When I ask how long it takes to finish a project, William says, “It takes as long as it takes.” He shows me the swinging cranes that lift heavy materials, the giant fan he traded a painting for, and a room he is working on.

We walk and talk, and then we sit down in his office and talk about his work and about art in general. The following is a recreation of part of our conversation:

Superstition Review: Have you worked with art galleries?

William Barnhart: I did for a time, but not anymore. Art galleries insulate the artist from the clients, because if the client and the artist are communicating, there really is no need for the art gallery. I like the communication with my clients. I can put my studio down anywhere, and my clients will come to me.

SR: That’s true, you have an actual client-artist relationship. What kind of mediums and materials do you work with?

WB: I do prints, paintings, sculpture. I like working with bronze, making sculptures. You know, bronze, it’ll be around for generations.

SR: I read that the sculpture you recently finished has gold on it. Do you think the value of the materials you use adds something to your work?

WB: I definitely want to use quality materials in my work. It’s not necessarily the value of the materials but the quality of them.

SR: I know some artists try to make social commentary with their art. What would you say is the message you are trying to convey with your art?

WB: Social commentary is definitely not the focus of my work. I want my art to be universal, to transcend the bounds of time. It’s more about relationship issues, about human emotions and the drama of the figure. It’s about the human experience.

We discuss other things, such as his creative process and why he chose that particular area to place his studio. But when I take leave of William Barnhart, print-maker, designer, painter, sculptor—with “more stripes than the tigers,” to use his words—what lingers most in my mind is the image of the high-domed building, the living space, the vibrant place of craft that is itself a work of art.

For more information about William Barnhart’s studio and his work, visit his website.