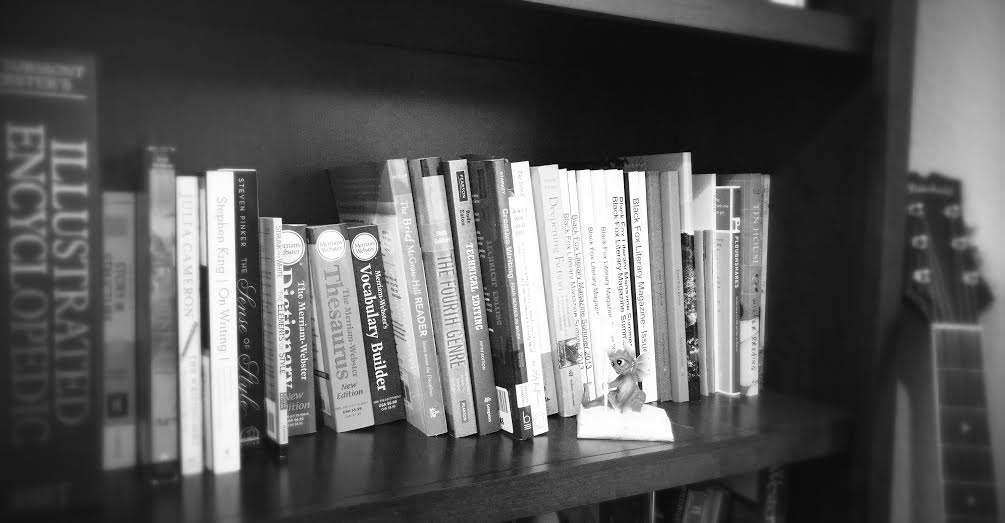

While I was working toward my degree at Arizona State University, I had the good fortune to stumble into a part-time position with the good people at Black Fox Literary Magazine. I started there as a copy editor and was surprised and delighted when Racquel Henry, one of the founding editors, asked me to help out with reading submissions. I know, because of my experience interning with Superstition Review, that helping choose which submissions make it to publication is an important (and coveted) role at a magazine. So I am proud of, and also humbled by, the opportunity to work in that capacity.

Because I am a writer, I try to be the reader my writer-self would appreciate most: someone with an appreciation for what it took to hit that submit button, someone with compassion, and someone who can set aside their bias and view each piece of work with some level of detached artistic objectivity. Hah! Well, two out of three ain’t bad. Though my intentions be honorable, I still bring an incredible amount of baggage to the page as a reader. I hope that my awareness of it somehow eases the weight of it; and I’m grateful that my preferences contribute in a meaningful way toward the goals set forth by the staff at Black Fox. Learning to navigate feelings of preference, and incorporate them with factual information about what is good in terms of craft, is a process.

On my very first day in Creative Writing class at ASU, the professor started talking about her aesthetic. She used words like dark, edgy, creepy, gothic, and raw; and expressed no small amount of enthusiasm over the emergence and acceptance of magical realism in the literary world. I was a little thrown at first, my own experience of the word aesthetic being only one of the available definitions: pleasing in appearance (Merriam-Webster). While I could see how a story could be viewed as aesthetically pleasing from a technical standpoint (and let no one underestimate the power of technical accuracy), I now understand the meaning and implications of the term aesthetic as it pertains to art, literature, and the power of reader preference. If I could whisper in the ear of every writer who submits a piece for our magazine to consider, I would say, “Whether or not we accept your work today is more about us than it is about you, so please keep trying.”

On my very first day in Creative Writing class at ASU, the professor started talking about her aesthetic. She used words like dark, edgy, creepy, gothic, and raw; and expressed no small amount of enthusiasm over the emergence and acceptance of magical realism in the literary world. I was a little thrown at first, my own experience of the word aesthetic being only one of the available definitions: pleasing in appearance (Merriam-Webster). While I could see how a story could be viewed as aesthetically pleasing from a technical standpoint (and let no one underestimate the power of technical accuracy), I now understand the meaning and implications of the term aesthetic as it pertains to art, literature, and the power of reader preference. If I could whisper in the ear of every writer who submits a piece for our magazine to consider, I would say, “Whether or not we accept your work today is more about us than it is about you, so please keep trying.”

This experience as a reader for a literary magazine has helped me to grow as a writer, both in terms of craft application and in the business of sending my work out for publication. I’ve learned that it really is important to follow submission guidelines. A well-crafted story or poem truly can speak for itself. While hombre might be all the rage at the hair salon, as a font choice it’s just annoying. That kind of formatting distraction prevents the reader from connecting with the story, may cost the magazine extra to include in their print publication, and in some cases, has been known to cause migraines. Either way, it’s probably not going to earn the story a thumbs up with the readers. So, out of respect for the publication I’m submitting to, and an earnest desire to have my work appear in their magazine, I follow their rules.

A clean submission with a professional cover letter, perhaps, has become part of my own developing aesthetic. Black Fox is blessed with hundreds of submissions each reading period, and we are usually reading and making decisions right up to the 12th hour! I have to confess, when I’m powering through the submission pile that last week or two, if I come across a cover letter that is addressed to <insert editor name here>, I’m going to skip it. Call me what you like.

Working on both sides of a publication, as a contributor and as a reader, gives me the opportunity to really immerse myself in the industry, and I am learning so much. Early on in my fiction workshops at ASU, one of my fellow students told me that it was a privilege to read my work. I was mortified by the attention. But I get it now. It really is a privilege, and an honor, to be on the receiving end of the submit button. Whether a piece of work tickles my fancy or not, whether the writer met the guidelines or not, I am humbled by the courage it took for that piece to reach me.