The submission process must be the most impersonal part of a writer’s career. The author has just spent days, weeks, or even years writing, editing, and workshopping the best piece of fiction they can muster. But without an audience, it’s just a piece of journal writing. Professors and other writing professionals will encourage the author to “get your work out there” and “you need a few rejection letters under the belt.” So this piece of written human soul gets crammed into an email and whisked away to a faceless submission editor.

Finding places to submit work to is the first part of this impersonal interaction. The best way to find a literary journal that will like your work is to read journals that have similar work to yours. The problem is, that the pieces that they are publishing may either A. be much stronger and more practiced or B. not anything like what you write, in terms of style. SmokeLong Quarterly is my favorite online journal, but my written work has not measured up to their level so far. I find this uneven balance when I am submitting work where I’ve either spent a lot of time reading a journal and realized that there’s no way my work stacks up. Or I’ve never heard of the journal, and think they must just be publishing anyone, why would I bother. Scanning through lists and call for submissions can feel like job hunting with incredibly vague parameters.

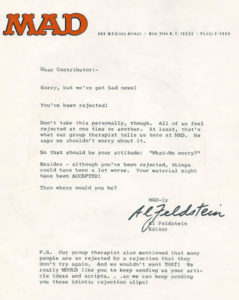

However, the worst part of this process is the rejection email. There’s never a right time or place to receive the email and it’s never quite worded the right way. A rejection email that sticks out in my mind said, “while we loved the absurdist normalcy of the piece, we regret to inform you…” I appreciated the time it took for them to write something personal about my work, but it left me questioning what that meant. I spent the next few days workshopping the email, trying to get a positive deconstruction of the narrative and what the character was trying to say to me. Needless to say, I didn’t get anywhere.

Being on the other side of this as a submission editor had a similar disconnect. We had almost three hundred fiction submissions. Three hundred is a relatively low number for some journals, but it set a record for Superstition Review. I found myself stuck looking at a neverending list of titles from strangers. They show up like an excel database, or some customer list. It’s very different than sitting across from someone in a workshop.

Writing the rejection email I ran into a similar conflict. Based on the rejections I’ve gotten the email should do the following; thank the writer for submitting, tell them no, and ask them to read the journal anyway. Which always feels inauthentic when on the receiving end.

The value in submitting can’t come from personal connection. Instead, it has to come from a place of personal growth. Only by submitting (and being on the other end) can an author learn to make mistakes and to take risks. Keeping a piece of writing private keeps it safe and for some people that’s enough. Exposing a piece of writing forces the author to grow their craft and skill by releasing that inhibition. Social media has exposed the extremes of our society. Most often, we only see something that is of extreme success or extreme failure. Small failures have to happen for any professional to grow. For writers that comes in the form of rejection letters. These are only small failures, and they must be overcome in order to grow. I hope that Superstition Review gets six hundred fiction submissions next semester and that many more small failures get to occur.