I realize the rhetorical purpose of this teaching philosophy is to convey my expertise as an instructor of creative writing. Having spent a year applying to jobs like this one, I’m well practiced in such arguments: I study writing pedagogy and carefully develop my syllabi. I show up to class on time, prepared, and smartly dressed. I take attendance by asking students fun questions about themselves, because I want to make them feel welcome and I am genuinely interested in getting to know them. I grade attentively and give constructive feedback on every assignment. I have a way of explaining the difference between passive and active voice that elicits laughter. By and large, I know what I’m talking about (I am, after all, a practitioner of my subject). My students tend to give me good rankings on evaluations and say nice things like, “This was honestly one of the best and most fulfilling courses I’ve taken.”

I realize the rhetorical purpose of this teaching philosophy is to convey my expertise as an instructor of creative writing. Having spent a year applying to jobs like this one, I’m well practiced in such arguments: I study writing pedagogy and carefully develop my syllabi. I show up to class on time, prepared, and smartly dressed. I take attendance by asking students fun questions about themselves, because I want to make them feel welcome and I am genuinely interested in getting to know them. I grade attentively and give constructive feedback on every assignment. I have a way of explaining the difference between passive and active voice that elicits laughter. By and large, I know what I’m talking about (I am, after all, a practitioner of my subject). My students tend to give me good rankings on evaluations and say nice things like, “This was honestly one of the best and most fulfilling courses I’ve taken.”

But don’t be deceived. I’m no expert. This is only my fifth year teaching writing to college students, and frequently, I feel inadequate to the task. I’m a better teacher than I was when I started, to be sure. But even on days when my students seem to grasp the importance of sensory detail, or when they enjoy the dialogue in a George Saunders story as much as I do, or when a writing prompt produces a lovely turn of phrase—I feel like I am failing them in some enigmatic but crucial way. I can’t shake the sense that the time I passed babbling about narrative stance would have been better spent listening to the thunderstorm outside.

Recently, I was walking through the woods near my house, thinking about John Steinbeck. In particular, I was thinking about what it took to write East of Eden. Steinbeck was an incredibly learned man—and I’m not referring to his formal education. Imagine the number of books, conversations, excursions, and ambles required to produce such a resonant story. As important (if not more) than his mastery of the craft of writing was his intimacy with American history, farming practices, Christian theology, eastern religion, philosophy, military hierarchy, Asian-American culture, small town politics, and California geography. What use would his talent and skill have been without his devotion to the art of observation? Steinbeck’s fine-tuned depictions of the natural world and of human motivations, relationships, and behaviors exist because he chose to cultivate depth and breadth within himself.

When I was a junior in college, my favorite professor told me (along with the other student in his fiction workshop) not to apply to M.F.A. programs in creative writing until we’d been out of school for a few years. His message: Live a little while longer, and then (maybe) you’ll have something worth writing about. I appreciated his honesty then, and I admire it now. And he was right: the experiences I’ve had over the last decade have both shaped me as a writer and given me meaningful material to write about. They’ve also made me into a more discerning, open-minded, and empathetic person. But I reject the notion that only time can give students the experiences and maturity required to write well. Aren’t depth of insight and breadth of knowledge something students can (and should) actively seek?

Lately, I’ve taken to dreaming up activities that might help students develop richer inner lives and more practiced powers of observation. I wonder what would happen if I gave them the following “assignments” to complete alongside their writing projects, textbook readings, and peer reviews:

- Spend ten hours over the course of the semester volunteering outside of the university setting at a food bank, nursing home, halfway house, homeless shelter, etc.

- Write a letter to someone you’ve wronged, and ask for forgiveness, OR do something nice for someone who’s wronged you.

- Attend a religious service for a tradition you are unfamiliar with.

- Break a law (but make sure not to hurt yourself or anyone else—and don’t get caught).

- Read a book on a subject outside of your major that interests you.

- Give a prized possession to someone who will appreciate it.

- Explore (on foot) a part of town you’ve never visited before.

- Go an entire day without talking.

- Stand up for somebody who’s suffering an injustice.

- Spend a weekend doing nothing but things you love to do.

- Skip class once this semester to have a nonacademic learning experience.

I believe that students who earnestly undertake these activities would write more engaging, nuanced, and descriptive pieces than what I’m used to seeing. I also know that assigning such endeavors is more likely to get me fired (or at least reprimanded) at my current institution than hired at yours. Liability issues aside, these assignments resist assessment, deemphasize performance and achievement, and don’t clearly connect to the “learning outcomes” desired by English departments. Moreover, they defy the business model embraced by many of today’s universities—a model that turns teachers into salespeople, students into customers, and education into a transaction.

But students want to be more than consumers of educational product. The first day of this semester, I asked mine to write down what they hoped to get out of my class. Here are some of their answers:

- “To help me see things from different points of view, to let my creativity flow, and to expand my horizons.”

- “I would like the opportunity to write freely and liberally as a release from the copious amounts of technical writing that my major has required of me.”

- “I have started songwriting and I think this class will help me with that.”

- “I believe that being proficient and expressive with the written language is important to personal growth.”

- “Mainly I wanted to express my emotions in writing and this was the class, in my opinion, that could help me do that.”

These answers reflect a hunger for more than credit hours, an easy A, a marketable skill, or a line for their résumés. These students want what a liberal arts education is supposed to provide—channels for participating in and finding fulfillment within a free society. Call it hubris or foolishness, but I think I can point them toward what they’re looking for, or at least join them in looking for it. It would be lovely if I could try without the fear of losing my job.

Should you choose to hire me (ha!), I will teach my students how to write with eloquence and stylistic flair. More importantly, I will cast them into a complex world filled with complex individuals and challenge them to respond with intelligence, curiosity, and compassion.

Thank you for your time and consideration.

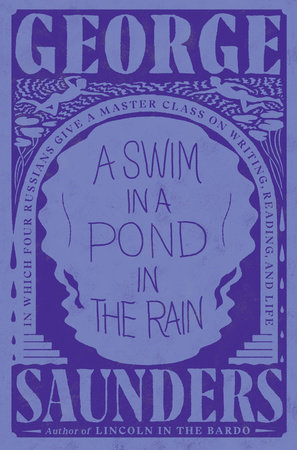

Today we are excited to announce that past contributor George Saunders has won the 2017 Man Booker Prize. George won the Man Booker Prize for his first full-length novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, a book based on the night Abraham Lincoln buried his 11-year-old son Willie in a Washington cemetery. Purchase your own copy by clicking

Today we are excited to announce that past contributor George Saunders has won the 2017 Man Booker Prize. George won the Man Booker Prize for his first full-length novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, a book based on the night Abraham Lincoln buried his 11-year-old son Willie in a Washington cemetery. Purchase your own copy by clicking