I met Michael Morse on the roof of Dia Center for the Arts in the early 90s. A mutual friend introduced us. It was summer or spring and the sun was going down over The Hudson River. Neither of us knew anyone at the party and so we were forced to drink our beers together. I remember, vaguely, not being too impressed with Michael. We were both poets who had, 2 years earlier, graduated from The Writers’ Workshop at The University of Iowa. I had recently moved to Brooklyn. His mother had recently died. Both of us, although I did not know it at the time, were adrift—floating on the docile waves of our mid-twenties with high aspirations undercut by low frequencies. What we had in common, we would soon find out, were many things: A deep love for The New York Mets, mothers with the same name, Carol, Roslyn High School (he, an alum; me, a teacher), Brooklyn, jazz, single malt scotch, and, of course, poetry.

I met Michael Morse on the roof of Dia Center for the Arts in the early 90s. A mutual friend introduced us. It was summer or spring and the sun was going down over The Hudson River. Neither of us knew anyone at the party and so we were forced to drink our beers together. I remember, vaguely, not being too impressed with Michael. We were both poets who had, 2 years earlier, graduated from The Writers’ Workshop at The University of Iowa. I had recently moved to Brooklyn. His mother had recently died. Both of us, although I did not know it at the time, were adrift—floating on the docile waves of our mid-twenties with high aspirations undercut by low frequencies. What we had in common, we would soon find out, were many things: A deep love for The New York Mets, mothers with the same name, Carol, Roslyn High School (he, an alum; me, a teacher), Brooklyn, jazz, single malt scotch, and, of course, poetry.

What’s interesting to me about my relationship with Michael is not that we have stayed best friends for almost 30 years or that we both love spring training and have endless amounts of hope in our hearts whether it be directed at The Mets or in our poetry trajectories, but that so much of our relationship has nothing to do with poetry. I suppose, in many ways, the reason we have stayed so close is that on the totem pole of what is important, poetry is down there at the bottom. Yes, when we first began to build our friendship we would wake early on Sunday mornings and meet at Harvest, a breakfast joint on Court Street, and share our work. But, it wasn’t the work that so much mattered—it was the grits, the hash browns, the occasional cup of coffee, the western omelette. It was the feeling, some indescribable geyser of love that grew out of necessity (as love always does), and a shared desire for a certain connection to the world. A world that always felt deep with possibility and horror. That kind of Existential horror that lead us to the F-train, to Coney Island, to the Boardwalk, to the beach, with a copy of Alan Dugan’s Collected Poems in our shared back pocket. There, at the shore, at the edge of the East Coast, we read out loud, to one another, “The Sea Grinds Things Up” completely shattered by that last line, “It’s a lonely situation.” And, ain’t it? But we had each other then like we have each other now.

This is a tale of poetry and friendship, a tale of friendship and poetry.

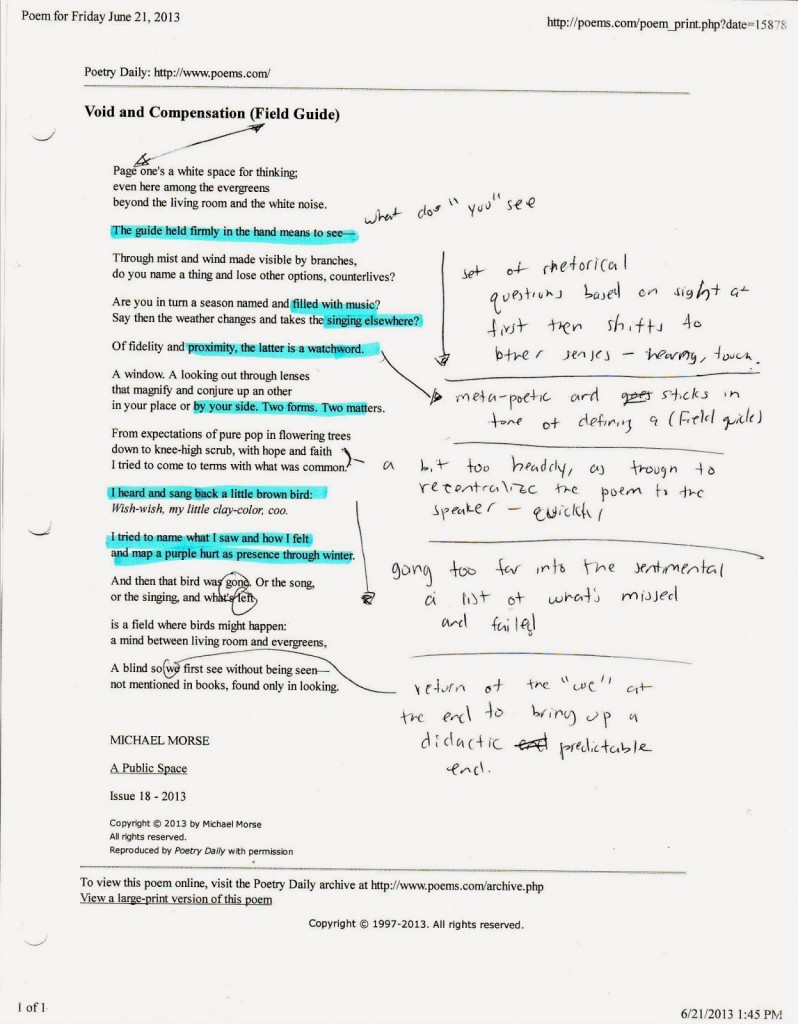

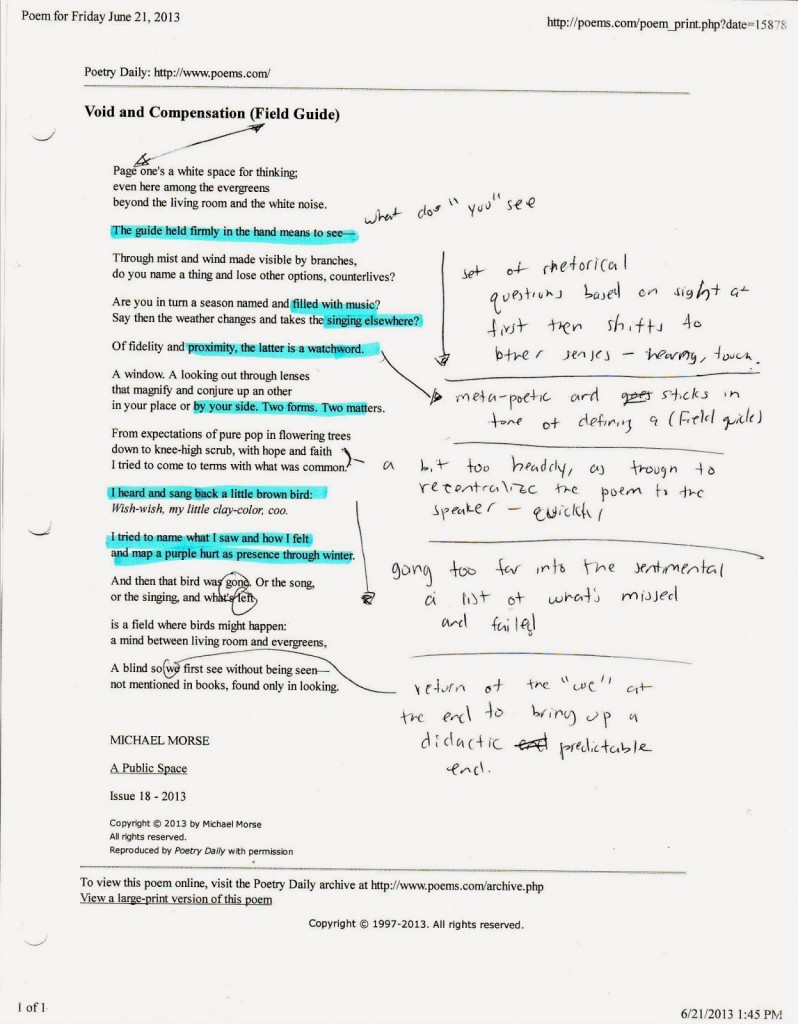

It took me 14 years to get my first book published after I left Iowa. It has taken Michael 21 years. 21 years after Iowa. Can you imagine? That’s an impossibly ridiculous number of years given his talent. Thank god for the folks at Canarium Press who, in their deep wisdom, decided to publish Michael’s first collection, Void and Compensation. As Michael’s friend it might seem disingenuous to speak on his work. He is my best friend. That might make speaking on his poems doubly disingenuous. Truth is, I don’t give a shit. They just floor me. Take for instance, “On Reading.”

On Reading

for Larry Levis

1.

When I read in bed, the book above me

held high, arm extended, I hold

the top right corner with my left hand

and let the finished pages rest on my wrist—

as if I’m denying the rays of a small sun

or keeping the printed word at bay.

It’s Chekhovian, how everything descends,

the protagonists, their stars and their sun.

This morning it’s my friend: I haven’t learned

to say his name in death since what he left

of his life on paper—tuberculin ink

spit up and out as darker rubies that

his body couldn’t keep and went to pages—

stains that snow crystal-by-crystal, persistent

and held above the head and kept at bay.

2.

It’s Valentine’s Day and I’m reading in bed.

I’m with my lover and we’re breaking up

although neither of us knows it yet—

I am reading and she is sleeping.

The book is still above me but I’m gone

(prescience disguised as daydreaming):

I’m at my lover’s apartment years later

and I’m holding her baby, not mine and yet

a ruby of my making, my ambivalence.

Love’s less and less about someday and more

of a resuscitation of someone:

Come, friend or lover and child fast asleep,

come dawn, all clock-tick and sparrow-chatter

and daylight starch waiting for ink and wanting—

The books are by the bed, and they are dead and ready.

The first time I read “On Reading” I got jealous. You know, that good kind of jealousy that starts—Oh fuck, I wish I wrote this but then slowly fades into appreciation and awe. I remember reading “On Reading” in Ploughshares where it was first published and feeling like I was stupid and in love at the same time. I kept thinking, How can you write a poem like that? So, I called him up to ask him. But, I didn’t really care; I just wanted to talk smack, that boy banter that makes us feel free. The love thing.

That’s how it is with Michael, with a Michael conversation—we talk poems which leads to sports which leads to Coleman Hawkins, which leads to Felix Milan, which leads to stupid banter. That’s the progression and the one that makes most sense. It’s one that I count on and cherish because it provides a holding, a containment that, on the surface, is built out of words but originates, if you will, out of the soil. I am lucky that Michael is a poet but if he weren’t a poet we’d still be best friends and that is why this friendship of ours has lasted. But, the poetry is a piece, no larger or smaller, than everything else. Shouldn’t that be the way it is? His poems are a celebration of that kind of everydayness that is the everydayness of human interaction, of friendship, of love, of romance and family. Take for instance “Bake McBride,” or “Tsimtsum,” or “Facebook.” Check this out:

Facebook

My friends who were and aren’t dead

are coming back to say hello.

There’s a wall that they write things on.

There are status updates. What are you doing right now?

For the most part, they seem successful.

They have children, which I can only imagine.

The hairy kid we called Aper, I haven’t heard

from him and wonder if in every contact

there are apologies inherent

for feelings hurt and falling out of touch.

You know what’s funny, once, a long time back, we were in a little guest house in Sag Harbor, 10 years ago, looking at all these poems on the floor. They were spread out like the ocean a few miles away. We stood over them trying to make sense of how they might fit together in a collection. 10 years later, here is that collection. 10 years. That’s how old some of them are, like whales, like accordions, that sing on and on over miles and years. All of them now in his first book, some of them go as far back as the ocean of Iowa. That’s history. It’s a history of his poetics and it’s a history of our friendship.

Void and Compensation is a triumph of perseverance. More than that, it is a triumph of love and words—the lasting power of both. It’s one of the great poetry books of the last quarter century. I say this as Michael’s best friend; I say this as someone who is a Poet; I say this as someone who has a general dis-taste for poetry. But, don’t take my word for it. Go get the thing and put it in your back pocket. Walk around the countryside with it. Get on the F-Train to Coney Island with your best friend and read “Rand McNally” at the ocean to make your own road map of love and friendship. These poems of Michael’s, you see, are about finding one’s way; they are all about the breaking of the waves, and the sound barrier inside the chest, broken in half.

Michael Morse is my best friend and so none of what I have written matters. It’s tainted with Technicolor subjectivity. But, I don’t give a shit. I sing the love songs I sing. You sing your own. That’s what’s important. That we sing them. Alone. To one another. I love Michael’s songs. The ones he has sung to me at The A&G Pork Store, at Shea Stadium, from the car on his cell, asleep on rocks in the middle of rivers in Pennsylvania, where and whenever. I love them as much as the ones in Void and Compensation— it’s own set list, concert, at The Garden, sold out performance, sung to 15,000 screaming fans, one after another, as lonely as they’ll ever be and never more thankful.

Hell, I am lucky to be in the front row, my left hand in the air, my right hand gripping tight a BIC lighter in this long and graceful encore that just keeps on going, shining the light.

We have some great news from past contributor Laura Esther Wolfson. Laura’s essay collection, Proust at Rush Hour, has won the 2017 Iowa Prize in Literary Nonfiction. The book is forthcoming from the University of Iowa Press in the spring of 2018.

We have some great news from past contributor Laura Esther Wolfson. Laura’s essay collection, Proust at Rush Hour, has won the 2017 Iowa Prize in Literary Nonfiction. The book is forthcoming from the University of Iowa Press in the spring of 2018. We have some great news from past contributor Laura Esther Wolfson. Laura’s essay collection, Proust at Rush Hour, has won the 2017 Iowa Prize in Literary Nonfiction. The book is forthcoming from the University of Iowa Press in the spring of 2018.

We have some great news from past contributor Laura Esther Wolfson. Laura’s essay collection, Proust at Rush Hour, has won the 2017 Iowa Prize in Literary Nonfiction. The book is forthcoming from the University of Iowa Press in the spring of 2018.