I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the political and the personal. When I was in graduate school, getting my MFA, my poet friends and I professed a slight scorn for poetry that was too or only or merely political. We spoke of the need for the individual voice, the lyric, the arena of mystery where a thing could not be defined by politics alone. We spoke with a what I now recognize as typical graduate school over-earnestness about how poetry had to exist in language first, as if language itself were somehow beyond or antithetical to the practice of politics. This now seems to me terribly naive, sign of a privilege we didn’t know we had. Now that I am older, and living in the America that is our America now, it seems to me, on the contrary, that everything is political, and yet the vexed crossing of the political and the personal still stands.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the political and the personal. When I was in graduate school, getting my MFA, my poet friends and I professed a slight scorn for poetry that was too or only or merely political. We spoke of the need for the individual voice, the lyric, the arena of mystery where a thing could not be defined by politics alone. We spoke with a what I now recognize as typical graduate school over-earnestness about how poetry had to exist in language first, as if language itself were somehow beyond or antithetical to the practice of politics. This now seems to me terribly naive, sign of a privilege we didn’t know we had. Now that I am older, and living in the America that is our America now, it seems to me, on the contrary, that everything is political, and yet the vexed crossing of the political and the personal still stands.

Everything is political. Everything is personal. This is both true, and untrue, and perhaps the more relevant question is how do they come together? What can we do as persons to speak out or engage in politics; more precisely, how can we do this without losing the distinctive strata of experience the personal gives us?

Recently, I read an article by Isreali philosopher Yuval Noah Harari in which he made a useful distinction. He said the important task was to look at what was real, and he pointed out how much of our power, our politics come from our capacity as humans to devise collective fictions. He goes on: “The best test to know whether an entity is real or fictional is the test of suffering. A nation cannot suffer, it cannot feel pain, it cannot feel fear, it has no consciousness. Even if it loses a war, the soldier suffers, the civilians suffer, but the nation cannot suffer. Similarly, a corporation cannot suffer, the pound sterling, when it loses its value, it doesn’t suffer.”

I thought of this last week when I saw that President Trump’s approval rating had risen—apparently, for there seemed no other conceivable reason, because he dropped a 22,000 ton bomb—a bomb so enormous commentators referred to it with almost unseemly glee as “the Mother of all Bombs,”—on an Isis training camp in Afghanistan. And, a few days before, he launched a major airstrike against Syria in retaliation for President Assad’s use of chemical weapons. The airstrike was large enough to make those on the scene feel “the heavens were falling,” and took out a few airplanes, a couple of runways, while not in any real sense impeding President Assad’s ability to wage war against his own citizens. For these acts, Trump was more often than not praised by major media “for finally acting presidential,” “showing the world he could be decisive,” and “demonstrating leadership.”

Track the suffering: 15 were killed in the Syrian airstrikes. The bombing in Afghanistan killed an estimated 94. Between 321,358 and 470,00 people have died in Syria’s civil war to date; 1 2,394 US soldiers have been killed in Afghanistan since 2001; over 26,000 Afghan civilians have been killed during the same period, with estimates of total Afghan deaths due to war-related violence or events related to the war rising as high as 360,000.

These numbers suggest the outlines of the “real story,” but for an American writer far from the actual battlefields over there, they leave unsettling questions. How do I bear witness? How do I take repsonsbility? Their suffering is not the same as mine. Am I qualified to speak of it? Where does my personal intersect with this political?

***

Here is a story from my life:

When I was a young child, and first went to school, I was relentlessly mocked because I had crooked legs due to a genetic illness. Every day at lunch ,a group of boys and girls would surround make fun of me, and dare me to run across the playground, which made them laugh because I could not for the life of me 1) run fast or 2) run in a straight line.

I had one friend, a girl called Nicky, who was as outcast as I was, though for less desirable reason. Nicki was thin and scrawny with mousy hair that looked as if it had been cut with nail scissors; she stammered when called on and burst into tears easily when frightened. When the group of kids on the playground got tired of making fun of me, they made fun of Nicki. Over the course of the year little-by- little I became bolder. I spoke back. I became good at telling tall tales, making jokes. I was still scorned, but ever-so-slightly less so.

One day a popular girl who had long been one of my tormenters took me aside. She wanted me to play a trick with them on Nicki. I was to ask Nicki to go with me to the edge of the plaground, our usual spot, under a large plain tree, where we sat and played with people we made out of seeds and grass. And there the others would jump out and frighten her.

I don’t actually recall the exact mechanics of how this was to work, but I do remember what happened. Nicki ended up facedown on the playground, sobbing as the others surrounded her and prodded at her with sticks. It is a blurred memory and one that, when it comes back to me, always, these fifty-some years later, makes me flinch. But the point is this—when it came down to it, I wanted to belong, more than I wanted to be true to my friend. I felt myself weak and I wanted to be strong, and I wanted this badly enough to behave just like any other playground bully.

I remember one other thing too. After a few weeks, the other kids got sick of me, and left me with Nicki again, and we resumed as we had before, sitting by ourselves at the edge of the playing field, eating our lunch and playing with our makeshift grass-and-seed dolls, but I don’t think it was ever quite the same as before.

This small story is, of course, not in the slightest “political,” nor does it on the surface have much to do with bombs in Afghanistan or airstrikes in Syria, but there is a kind of affinity, for what is my story, after all. if not an allegory of power or the longing of even the weak to seize it and be strong? It suggests, too, how suffering and cruelty can result from that longing or how little there is in the world to defend the most vulnerable.

***

The personal and the political. One thing they share is both are in some degree made of stories, stories in which it is always hard to parse the lie from the truth. In her remarkable lecture, given on winning the Nobel Prize, “Every Word Knows Something of a Vicious Circle,” Romanian novelist, Herta Muller, like Yuval Harari, concerns herself with the difficulty of telling our fictions from “reality,” truth from lie. She writes of this problem as one bound up in and also, perversely, only able to be solved through language itself—the process of thought, speech, and, especially, writing. The essay begins almost tenderly:

DO YOU HAVE A HANDKERCHIEF was the question my mother asked me every morning, standing by the gate to our house, before I went out onto the street. I didn’t have a handkerchief. And because I didn’t, I would go back inside and get one. I never had a handkerchief because I would always wait for her question. The handkerchief was proof that my mother was looking after me in the morning. For the rest of the day I was on my own. The question DO YOU HAVE A HANDKERCHIEF was an indirect display of affection. Anything more direct would have been embarrassing and not something the farmers practiced.

Muller parses how words or discourse give us ways of expressing through indirection true or important things about ourselves we won’t or can’t simply say. How would her mother ever declare “I love you” except by asking the question about the handkerchief?

Yet Muller’s essay quickly darkens. She grows up and works in manufacturing plant. There, she is approached by an agent of the Romanian Securitate. He uses a variety of tactics to appeal to her, flattering her first, then abusing her, all with the intent of persuading her to become an informer, spying and reporting on her colleagues at the factory. Muller refuses, and almost instantly finds herself an outcast. Lies are spread that she is a spy. Everyone knows this is not true, but everyone is afraid. Her best friend refuses to let Muller into her office: I can’t let you in. Everyone is saying you’re an informer.

Her desk is repossessed, her status stripped away.

Even if most of us have not lived thought such terror, we have experienced situations where the words around us became suddenly a lie, or where we do not know how to assert our own truth in the presence of what seems an overpowering mandate to think or be a certain way. Or where people or words actively betray us.

Once cast out, Muller spends her days sitting on the factory staircase, reading the dictionary for she has nothing else to do. Painstakingly, she learns all the words that have to do with stair: “HAND is the direction a stair takes at the first riser. The edge of a tread that projects past the face of the riser is called the NOSING…nosing and hand, so the stair has a body “ In finding the story words tell of the objects around her, she sees how they can create another world—not quite the world; yet a truth of the world:

Whether working with wood or stone, cement or iron: why do humans insist on imposing their face on even the most unwieldy things in the world, why do they name dead matter after their own flesh, personifying it as parts of the body? Is this hidden tenderness necessary to make the harsh work bearable for the technicians? Does every job in every field follow the same principle as my mother’s question about the handkerchief?”

Mueller is fascinated that it is precisely in the slippage of words, their materiality which has an affinity with, but is not the same as, the materiality of the world that provides words with their curious capacity to see inside or to reform or remake one’s relation with the world, even in the most desperate of circumstances:

The sound of the words knows that it has no choice but to beguile, because objects deceive with their materials, and feelings mislead with their gestures. The sound of the words, along with the truth this sound invents, resides at the interface, where the deceit of the materials and that of the gestures come together. In writing, it is not a matter of trusting, but rather of the honesty of the deceit

I love the phrase she uses here: “honesty of the deceit,” for when I think of writing, both as a political and a personal act, it is the imperative toward honest deceit that catches me the most. Often, when I write a poem or an essay, and I try to include something I have seen, I am always conscious of my failure, the way in which what I write is never quite the thing itself. At the same time, I know when the deceit is most honest, the words catch something that is true in a lyrical and political way about experience. Often this occurs when I am furthest from being strong or in control, but rather when my vulnerability is most acute, when the only means I have of bridging the gap I feel between myself and what is around me is through the materiality of the words themselves.

In finding herself under a dictatorship, unable to speak in a way that would be believed, Muller becomes obesesed with writing, with studying, simply, the words for things:

….what can’t be said can be written. Because writing is a silent act, a labor from the head to the hand.I talked a great deal during the dictatorship…Usually my talking led to excruciating consequences. But the writing began in silence, there on the stairs, where I had to come to terms with more than could be said. I reacted to the deathly fear with a thirst for life. A hunger for words. Nothing but the whirl of words could grasp my condition….

This week when I read of Trump’s newly enhanced presidential mien, and saw the stories about the war that might be coming, and thought about how powerless I—and most of us—feel, and how the language of the public arena itself seems to defeat our efforts to change or mend or heal what the wounded world is doing around us, I thought of Meuller’s speech, and the notion of words as a way of filling the gap, their honest deceit, or that they, through their matter, will somehow penetrate or pierce the consequences of the fictions we live by each day. Muller writes:

The more that which is written takes from me, the more it shows what was missing from the experience that was lived. Only the words make this discovery, because they didn’t know it earlier. And where they catch the lived experience by surprise is where they reflect it best. In the end they become so compelling that the lived experience must cling to them in order not to fall apart

You could mull over what this means for a long time, but I think what I take from it—is simply this, only in the words can we hold the distinction between what is real and the unreal ideologies that make up so much of our lives at this moment. We can remember that it is only persons who suffer and, more, we can without deliberation or foreknowledge begin to trace what is missing from the lived experience of our time.

Bio: Jaime Faulkner is a junior at Arizona State University majoring in Communication. She is currently the Nonfiction Editor for Superstition Review, as well as a volunteer editor with Four Chambers Press. Upon graduation, she hopes to work in publishing as an editor and author.

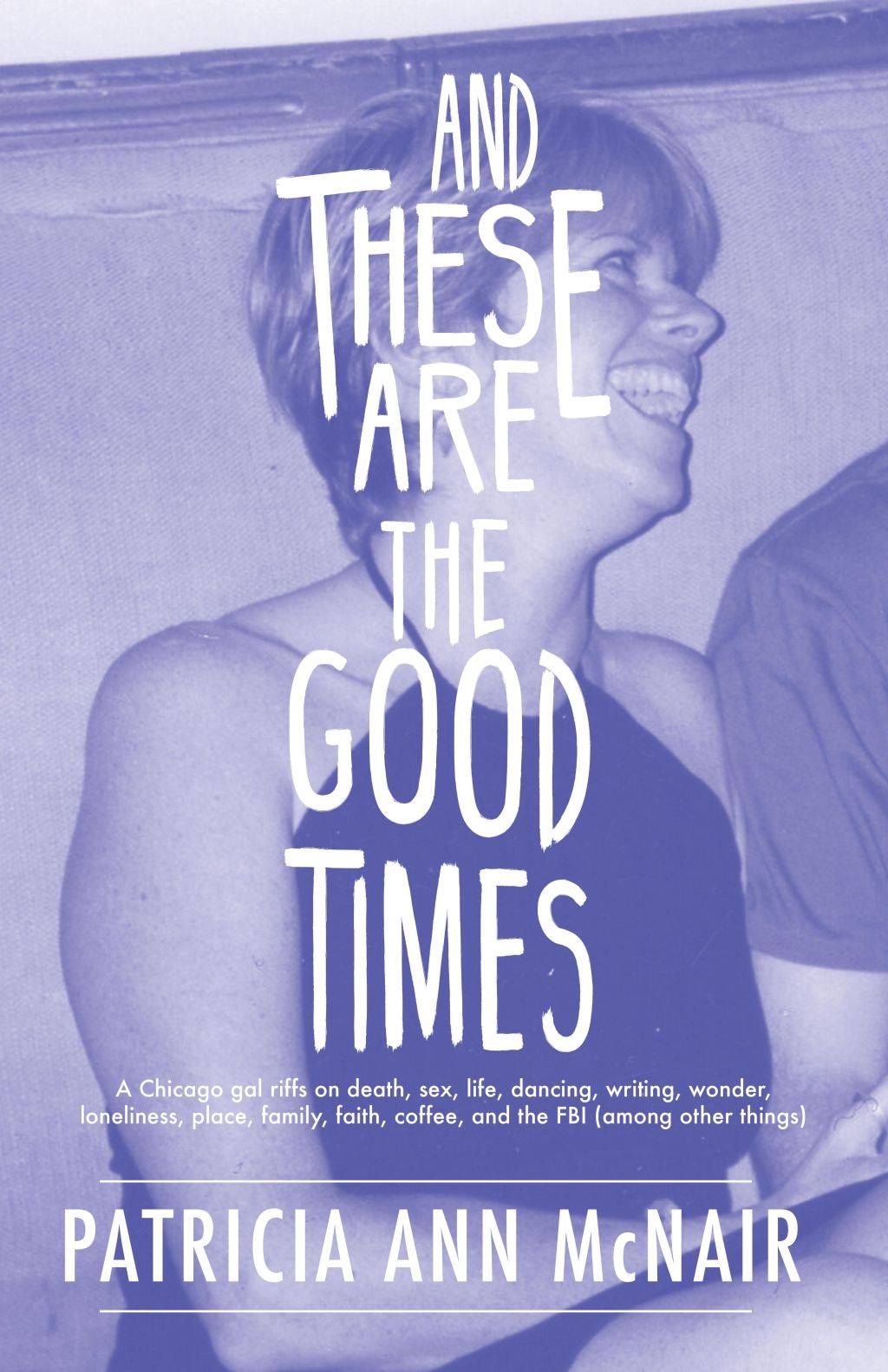

Bio: Jaime Faulkner is a junior at Arizona State University majoring in Communication. She is currently the Nonfiction Editor for Superstition Review, as well as a volunteer editor with Four Chambers Press. Upon graduation, she hopes to work in publishing as an editor and author. Hello everyone! Today we are excited to share that past contributor Patricia Ann McNair has a new book out titled And These Are The Good Times, a collection of essays which include a couple of pieces Patricia wrote for our very own blog.

Hello everyone! Today we are excited to share that past contributor Patricia Ann McNair has a new book out titled And These Are The Good Times, a collection of essays which include a couple of pieces Patricia wrote for our very own blog. We have some great news from past contributor Laura Esther Wolfson. Laura’s essay collection, Proust at Rush Hour, has won the 2017

We have some great news from past contributor Laura Esther Wolfson. Laura’s essay collection, Proust at Rush Hour, has won the 2017  I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the political and the personal. When I was in graduate school, getting my MFA, my poet friends and I professed a slight scorn for poetry that was too or only or merely political. We spoke of the need for the individual voice, the lyric, the arena of mystery where a thing could not be defined by politics alone. We spoke with a what I now recognize as typical graduate school over-earnestness about how poetry had to exist in language first, as if language itself were somehow beyond or antithetical to the practice of politics. This now seems to me terribly naive, sign of a privilege we didn’t know we had. Now that I am older, and living in the America that is our America now, it seems to me, on the contrary, that everything is political, and yet the vexed crossing of the political and the personal still stands.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the political and the personal. When I was in graduate school, getting my MFA, my poet friends and I professed a slight scorn for poetry that was too or only or merely political. We spoke of the need for the individual voice, the lyric, the arena of mystery where a thing could not be defined by politics alone. We spoke with a what I now recognize as typical graduate school over-earnestness about how poetry had to exist in language first, as if language itself were somehow beyond or antithetical to the practice of politics. This now seems to me terribly naive, sign of a privilege we didn’t know we had. Now that I am older, and living in the America that is our America now, it seems to me, on the contrary, that everything is political, and yet the vexed crossing of the political and the personal still stands. Reading it here, you can easily figure it out, because you can return to the text and reread, but aloud, this gets people (nearly) every time, because once they hear the numbers, they start trying to do arithmetic, thinking you’re going to ask them how many people are left on the bus. I apologize for stating the obvious. The point of the riddle is misdirection, a subversion of expectations that’s satisfying in its cleverness instead of frustrating. This is just one example of this principle in action. One might easily point to most Hollywood movies, for instance, with their twists and turns to keep viewers guessing. I know this, and you know this, but I hope it’s worth revisiting briefly here, as I retread some of my own path to realizing it (making it real), and applying it to essay writing, specifically.

Reading it here, you can easily figure it out, because you can return to the text and reread, but aloud, this gets people (nearly) every time, because once they hear the numbers, they start trying to do arithmetic, thinking you’re going to ask them how many people are left on the bus. I apologize for stating the obvious. The point of the riddle is misdirection, a subversion of expectations that’s satisfying in its cleverness instead of frustrating. This is just one example of this principle in action. One might easily point to most Hollywood movies, for instance, with their twists and turns to keep viewers guessing. I know this, and you know this, but I hope it’s worth revisiting briefly here, as I retread some of my own path to realizing it (making it real), and applying it to essay writing, specifically. Writing anything worthwhile is an invitation to risk. Besides being largely subjective, risk is many faceted. Risk may be taking on the mantle of a writer, and foregoing a stable career. It can also be thought of as the effort you take to draw a reader in, or it may be what you are willing to do to your characters. Risk can also mean stretching oneself and tackling unfamiliar, outright uncomfortable, genres. But are any of these really risking all that much?

Writing anything worthwhile is an invitation to risk. Besides being largely subjective, risk is many faceted. Risk may be taking on the mantle of a writer, and foregoing a stable career. It can also be thought of as the effort you take to draw a reader in, or it may be what you are willing to do to your characters. Risk can also mean stretching oneself and tackling unfamiliar, outright uncomfortable, genres. But are any of these really risking all that much?