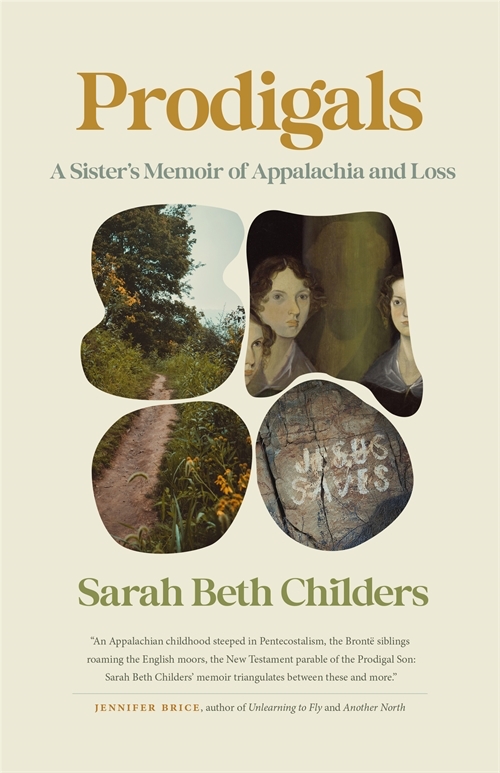

Congratulations to SR Contributor Sarah Beth Childers on her forthcoming book, Prodigals: A Sister’s Memoir of Appalachia and Loss.

Prodigals is a series of lyric essays of loss and resistance told in the voice of an Appalachian storyteller.

The book examines how Childers’ brother’s story was both universal and uniquely Appalachian. While the familiar story of the prodigal son carries all its assumed baggage, the Appalachian setting of Prodigals brings its own influences. Childers foregrounds the Appalachian landscape in her narrative, depicting its hardwood forests, winding roads, mining-stained creeks and rivers, hill-clinging goats and cows, neighborhoods and trailer parks tucked between mountains. The Childers family’s fervent religious faith and resistance to medical intervention seems normal in this environment, as is their conflicting desires to both escape from Appalachia and to stay forever at home.

Prodigals weaves in the stories of other famous prodigals, including the alcoholic brother of the Brontë sisters, Jimmy Swaggart, the fallen televangelist; Robert Crumb, her brother’s beloved author of racist and sexist comic books; and Childers herself. The story examines the role of prodigals within the intimate tapestry of family life and beyond—to its larger sociocultural meanings.

Read some of the book’s reviews:

“An Appalachian childhood steeped in Pentecostalism, the Brontë siblings roaming the English moors, the New Testament parable of the Prodigal Son: Sarah Beth Childers’ memoir triangulates between these and more. From the outset, it raises the question of who the prodigal is—the younger brother Childers loved and lost, too young, to mental illness, or Childers herself, who left West Virginia and her insular family to become a writer and professor. In prose that’s full of swerves and surprises, Childers tells and retells her brother’s story. This telling is an act of loving retrieval—even a kind of return. Riveting, luminous, memorable. I’ve read it three times and can’t wait to begin again.” — Jennifer Brice, author of Unlearning to Fly and Another North.

“Prodigals is about the author’s grief as she explores—via memory, via writing, and via time—her brother Joshua’s mental illness and his loss. She came from a family that did not ascribe names and diagnoses to mental illness, no less Joshua’s, and she must not only find a variety of definitions for loss, love, and relationship but also for herself. This is a journey of self, intellect, and history, toward understanding.” —Karen Salyer McElmurray, author of Wanting Radiance.

“A gorgeous meditation on family, place, and loss. In revisiting the life of her beloved brother, Sarah Beth Childers insists on bearing witness to people and places as they are while contemplating those who stay and those who leave, and the wide pulsing spaces left in their wake. Captivating and clear-sighted. A beautiful book.” —Sonja Livingston, author of Ghostbread.

Sarah Beth Childers is the author of Shake Terribly the Earth as well as numerous publications in literary journals and anthologies. She is an assistant professor of English at Oklahoma State University and lives in Stillwater, Oklahoma.

View the creative nonfiction essay “Beagle in the Road” by Sarah Beth Childers in issue 20 of Superstition Review.

Prodigals: A Sister’s Memoir of Appalachia and Loss, released on September 1 from the University of Georgia Press’s Crux Series in Creative Nonfiction. Purchase the book here.

Joshua and his three sisters on his 7th birthday. Sarah Beth is in the Myrtle Beach shirt.

Joshua and his three sisters on his 7th birthday. Sarah Beth is in the Myrtle Beach shirt.