Some writers love to talk about their “writing process.” I am not one of those people. I could say it’s because “process” reminds me of something you do to meat, or because “processing” is what people say they’re doing after something horrible happens. The truth is that I’m a private person— a genteel way of saying that I frequently feel simultaneously embarrassed and protective of myself, especially the way my mind works (or doesn’t) in my off-hours from academia. And yet, whenever I sat down to think of some account I could give to this fine website, this set of very personal metaphors occurred, and no matter how much I tried nothing more clever or articulate arrived.

Some writers love to talk about their “writing process.” I am not one of those people. I could say it’s because “process” reminds me of something you do to meat, or because “processing” is what people say they’re doing after something horrible happens. The truth is that I’m a private person— a genteel way of saying that I frequently feel simultaneously embarrassed and protective of myself, especially the way my mind works (or doesn’t) in my off-hours from academia. And yet, whenever I sat down to think of some account I could give to this fine website, this set of very personal metaphors occurred, and no matter how much I tried nothing more clever or articulate arrived.

The truth is that often I am surprised to find that I have a poem, the same way one sometimes has an erect nipple—maybe the room is cold, maybe that picture is crooked, maybe someone died—years ago—and you just remembered. Sometimes I have a poem, and sometimes I can’t remember that Allison Horschel* is dead.

She ran cross-country with me in high school. I always liked her in the way, when you’re thirteen, you like everyone who seems braver than you are. She’d hock and spit to show people the way to pronounce her Germanic last name. HOR-schel. We weren’t friends. She was older and loud and funny and crass, and the last time anybody I knew saw her alive she was being stuffed into the back of a cop car in the mill hill—a tiny neighborhood of almost identical houses built by the textile mill that had once dominated the town. At the time of this supposed arrest (“supposed” because, as is the rule in small towns, the truth can get quite bent in successive tellings), she had already graduated; I was still cutting through the mill hill to train for meets.

A few years later, after I moved away to college, my best friend C. had to tell me three times that Allison Horschel was dead—on separate occasions, months apart, because I kept asking after her. C. looked at me in disbelief each time—don’t you remember she’s dead. She died. A horrible car accident.

But I never remembered right away. To say that I felt like a heel each time would be putting it mildly. It was as if my mind just rejected the information—it felt wrong, so it couldn’t be true. At that age I still thought of home as a stage set I had momentarily walked away from, where I could return whenever I wanted, pick up the props and the people as if nothing had changed. She had died on C.’s birthday. Neither of us had spoken to her in years.

Another way of saying it: sometimes a poem is a small expectation breaking—like a knot of hair you can’t untangle. You pull it hard and you let it snap, rip out of your head. It always surprises me—how tough hair is, and how odd it is to see it disconnected from the body. An acquaintance, out of context. Uncanny.

Several friends have told me—as a gesture of what I would like to believe was affection— that after not seeing me for months, years even, they’ll find a long red hair in the pages of a book, or sealed up in a bag of sweaters, or they’re sweeping up getting ready to move house, and they think they could make a wig, really, out of what’s there. I want to believe that love is just such a contaminant— that when separated what we leave behind can be something so personal, so irritating, with the same gestures towards permanence and intimacy.

In the Song of Songs 6:6, the beloved’s teeth are compared to a flock of wet sheep emerging from the water. This analogy is disgusting and therefore permanent to my memory. When I was younger, I never understood describing the parts of a lover in terms of dirty farm animals. Now it makes some sense to me. Real closeness to anybody is never antiseptic or invulnerable. Teeth are wet because they live in the mouth. We are never as clean in our interactions, or in our metaphors, as we mean to be. Every comparison is a stretch.

One of the things I miss about the cows that used to live next to my parents’ property is their smell, the heaviness of it, the steam rising off their urine in the winter. I loved the way their eyes followed you as you walked. According to animal behaviorist Temple Grandin, if you lie down in a pasture and are still for long enough, the cows will circle around to look at you. Maybe lick you. I never thought to try that. I think at the time I would have been too afraid, too squeamish. They lived in their country; I lived in mine, for the most part. Good fences, etc. But that didn’t mean I never put my hand out for their snouts. They sometimes gave them, and let me pet their blazes— the weird imperfect stars of hair that grow between the eyes.

All of this to say, I guess, that I’m still here, holding up a hand. I have not yet lain down in green pastures, so to speak. But I do the work, and wait. Sometimes another hand happens to my hand, sometimes not. Sometimes there are poems. I am told, but do not remember, that many winters of my early childhood, my father would choose a cow, go with the neighbor to the abattoir, and then there’d be a freezer full of bloody meat for us to eat. What I do remember is that I liked drawing on butcher paper on occasion—even though it isn’t the best at taking pigment—because one side had a pearly feel, like skin. Impermanence, intimacy, death. There you are.

I visit home now and eat the soups and cornbreads that have contained many lives. I remind myself of Allison. I fill my cup back up with ice. It is summer in South Carolina— hot and damp. I remember the ratty ties we all wore in our hair in high school, tangled tight to our heads, and how we had to rip them out after running miles on throbbing shins and bloody blisters. When I am finished with my drink I dump my remnants in the sink, ice melted down to half-moons. I make another metaphor.

*not her real name

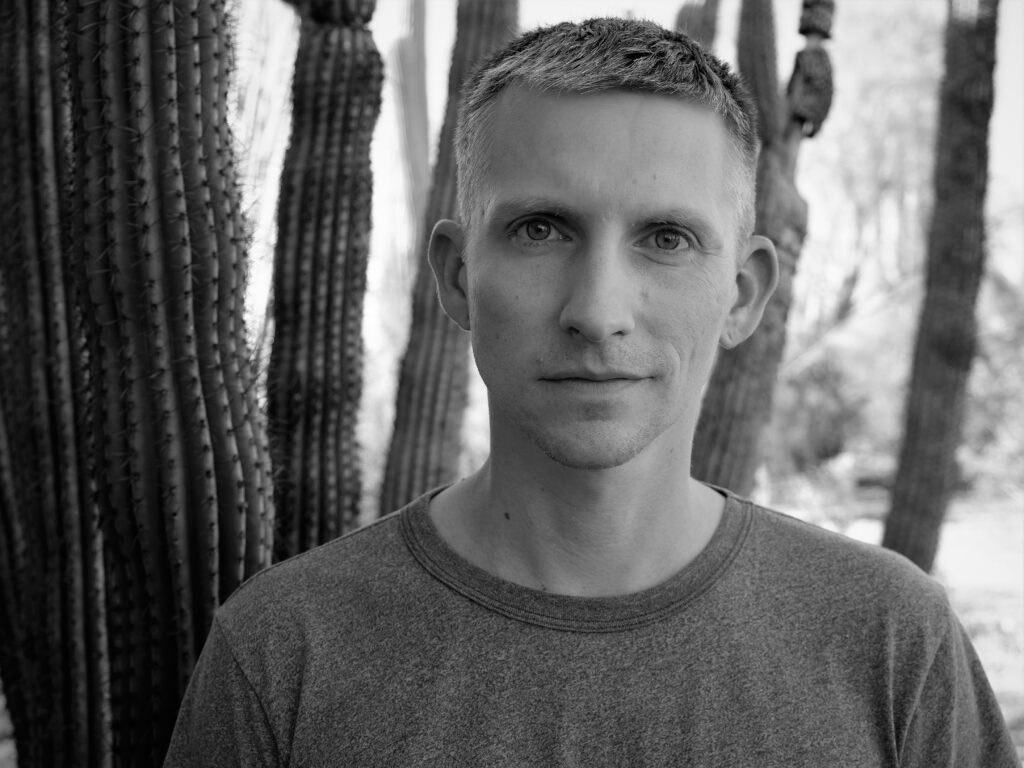

Joshua and his three sisters on his 7th birthday. Sarah Beth is in the Myrtle Beach shirt.

Joshua and his three sisters on his 7th birthday. Sarah Beth is in the Myrtle Beach shirt. Today we are pleased to feature author Aaron Reeder as our Authors Talk series contributor. In his podcast, Aaron provides insights into his poems, “Untangling” and “Failed Poem for My Mother,” both published in Issue 18. He reveals that, when he was writing these poems, he was interested in the systems people fall back on to deal with trauma and grief, specifically the system of family.

Today we are pleased to feature author Aaron Reeder as our Authors Talk series contributor. In his podcast, Aaron provides insights into his poems, “Untangling” and “Failed Poem for My Mother,” both published in Issue 18. He reveals that, when he was writing these poems, he was interested in the systems people fall back on to deal with trauma and grief, specifically the system of family.