“Your characters are so stupid,” the woman said. She sat at the other end of the table, directly across from me. It was a bright blue winter day, and the book club met high over the city, with views of the frozen lake and of snow piles going gray in the gutters. “I felt like slapping some of them!”

“Your characters are so stupid,” the woman said. She sat at the other end of the table, directly across from me. It was a bright blue winter day, and the book club met high over the city, with views of the frozen lake and of snow piles going gray in the gutters. “I felt like slapping some of them!”

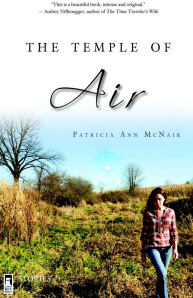

Okay, maybe this isn’t exactly what she said, this bit about my stupid characters, but it was something like that. (She did say the slapping part, though.) I’d been invited to speak with the book club about my collection of short stories, The Temple of Air, and I was, as I always am by these invitations, honored. I relish the opportunity to speak with readers; I’ve visited book clubs in living rooms and restaurants, shared brunch and dinner and coffee and drinks with avid and curious readers of all ages; I’ve read to them, talked with them, answered questions, filled them in on what parts of the book are “true” and what parts aren’t. (Yes, I knew identical twin brothers who dressed alike into their forties; no, they never murdered anyone that I know of. Yes, I hit a deer once with my car; yes, I had a neighbor whose husband shot half her face off; no, I haven’t had a mastectomy; yes, I have been unfaithful; no, I was never part of a cult.)

Perhaps you might discern from the parentheticals above that my book is not a particularly light read. There aren’t a lot of happy endings (although some I’d call bittersweet) and my characters get into trouble—often of their own making. And this book club lady in front of me (as well as a number of the other readers around the table) did not like that.

“Why didn’t he do something?”

“Why didn’t they stop him?”

“Why didn’t she get out of there?”

And then what, I wish I would have asked. Where’s the story in that?

Imagine The Grapes of Wrath if the Joads had turned back, got out of there, gave up their journey. The family, Steinbeck’s creation, shrinks by death and desertion, and yet they plod on. We, as readers, root for them, even though we are fairly certain that things will not turn out well. No happy endings here. And literature is all the better for it.

In a recent interview in The Writer’s Chronicle, Richard Bausch said, “…the thing that produces change is trouble. Even the happiest event is fraught with it, because we all know that the one promise life always keeps is suffering. Loss. Confusion. Grief. And writing about all those things matters because the subjects themselves matter.” He said as well, “…I’m always interested in the hurt people carry around.”

Me too.

I remember when I first read Raymond Carver. I came to him late-ish in life, like I did the active pursuit of writing. I’d dropped out of college and wasted time, bartending and managing a gas station, and finally spending a chunk of my twenties and thirties working in the financial markets in Chicago. And it was on a lunch break that I wandered into a bookstore (trying to get as far away from the noise of the open outcry on the trading floor as I could) and found What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. I’d been a big reader as a kid, as a teenager. But it had been a long, long time (for some reason) since I’d read much of anything besides the daily paper and my horoscope. This collection of stories was a slim one, and, having fallen out of the practice of reading, I found its skinniness appealing. I stood in an aisle among fiction titles and other lunchtime browsers and read “Popular Mechanics,” the very short story about a couple who divide their things as they pull their marriage (and their baby, the reader comes to understand) apart.

“Holy sh…” I whispered to myself at the brief and stunning story. I turned the pages, looking for another –well—gut punch, I guess.

Still standing, I read “The Bath.”

“You can do that?” I don’t know if I said this out loud, but whenever I think about that day in the bookstore decades ago (and I think about it often), I hear those words in my head. “You can do that?”

What I meant: you can write a story that ends in such a tragic and bleak way that it hurts like looking at something too shiny, too beautiful, and make your reader come back for more? My reading history had held mostly popular fiction, the books my girlfriends shared full of wish fulfilment and happy endings, or in school, stories with lessons, morals. I think it was all of that goodness, happiness, and lesson teaching that drove me away from reading in the first place. Finding a happy ending or moral in books and movies is easy, like microwaving a Hot Pocket for lunch. Happy, moralistic endings are sweet and comforting but ultimately without much nourishment and far from satisfying. I had grown tired of Hot Pockets.

The book club high above the city wanted (as some book clubs do) happy endings; not even the endings of my stories that I consider to be hopeful and bittersweet, nor the moments inside the stories that provide grace, caring, human connection, were enough for them. I told them I don’t often do happy endings, and they were disappointed. I was disappointed, too, that they would rather leave the pages of a book happy than curious and longing. If everyone lives happily ever after, then we don’t need to wonder about them anymore, do we? I passed up striving for the happy ending in order to try to create something that might be beautiful and moving, that might make me ache a little. For me as a writer, as a reader, reaching an ending where I find beauty and where I am moved, even if it’s a sad ending, makes me happy. But I didn’t tell them that, I hadn’t yet put it into words for myself. Even so, I don’t think it would have mattered.

“I was even starting to worry about you,” the woman at the other end of the table said (like I lacked some sort of moral fiber,) conflating the sorry parts of my characters’ lives with my own.

I have a good and happy life. I do. A solid job. A caring husband. Cats and travel and friends. And yet, some of the most remarkable moments that I carry with me, that I have been exceptionally moved by, changed by, stunned by, are these: the unexpected news of the death of my father when I was fifteen and the way one of my brothers sunk to the floor in grief and despair; my nephew, afraid of me for some reason on a sunny afternoon, dashing across a wet patio and slipping, scraping his knees and hands and crying in embarrassment and pain; a grade school guidance counselor dabbing her own eyes as she told me of my brother’s attempt at suicide; my mother dying in the middle of the night while I held her; coming home to an empty apartment after my first husband moved out, the hollow sound that came from the lock as I turned it.

These are the moments I want to tell, to write, the ones that leave me a little raw, that hold love and loneliness and memory and pain and suffering and survival. “Beauty is created out of the labor of human hands and minds. It is to be found, precarious, at some tense edge where symmetry and asymmetry, simplicity and complexity, order and chaos, contend,” the chemist and poet Roald Hoffman wrote.

“Your characters are so stupid,” the book club lady said. Or something like that. And what I now wish I had said: “Yes, yes they are. And so are you. And so am I.” Because let’s face it, we are all just stupid people, carrying our hurt around. Even the smartest among us make mistakes, take the wrong turn, sit when we should stand up, drop the thing we should catch. We are fallible and we are resilient. James Salter said to the Paris Review: “I deem as heroic those who have the harder task, face it unflinchingly and live.” Live, Salter said, not triumph.

And happy endings or no, this is what I want. I want my characters, these stupid people, to face it (whatever it is) unflinchingly, I want them to carry their hurt around, I want them to stand at the tense edge where order and chaos contend. And most of all, I want my characters, my stupid characters, to live.

This Tuesday, we are proud to feature a podcast of SR contributor Laurie Uttich reading her poetry from Issue 17.

This Tuesday, we are proud to feature a podcast of SR contributor Laurie Uttich reading her poetry from Issue 17.