I am good at waiting. Good in the sense that waiting could be my vocation. Like a professional mourner, I am skilled at hollowing out all but the most immediate demands of body and mind and instead substituting performance. Waiting demands that I occupy myself with small and useless tasks in order to perform busy-ness. I am a body in the chair until a body can be made useful, and speak.

I am good at waiting. Good in the sense that waiting could be my vocation. Like a professional mourner, I am skilled at hollowing out all but the most immediate demands of body and mind and instead substituting performance. Waiting demands that I occupy myself with small and useless tasks in order to perform busy-ness. I am a body in the chair until a body can be made useful, and speak.

Waiting is part of the in-between that Charles Baxter describes in his essay on stillness. He describes the amorphous space of nothing as being shaped by the action that frames it. The scenes of talking in Pulp Fiction, he says, are rendered possible by the violence that punctuates them. A hallway is only a hallway because of where it begins and ends. When we turn our lives into narrative we choose the beginnings and the ends to describe, those landmark points where action occurs. But such a description is possible only afterward, and not during.

When I am waiting I am concerned about time. The time bleeds away from the waiting body, dissolving harmlessly into no time at all. It flows along with the second hand until I am no longer conscious of every moment. When waiting, there could be no time at all. Except there is still the time of the body: processing, transforming, synthesizing food into calories, energy to the cells, nutrients to the bloodstream, awakening acid. Eventually the body calls us away from waiting, away from the book, to attend to its relentless needs.

Lately I have spent some time in emergency rooms and hospitals, not as a patient but as an observer. Family. Are you sisters? They always ask. Sometimes I just say no. Sometimes I say I’m her wife, at which point they straighten, either apologetic or embarrassed for us both.

As with so many emergency room visits, the reason for arriving was not immediately clear. It was, perhaps, an abscess, a post-surgical complication; it might have been infection, or perhaps a ruptured endometrioma. The last ER visit was prolonged. I was attentive to the beginning (3:30 a.m.) and the end (8:30 p.m., upon transfer to a neighboring hospital). I called family. I texted friends. I researched. Mostly I waited.

Afterward, I would try to arrange my thoughts into a narrative, a cohesive order, but they became jumbled, unwieldy. Pain and the attempts to quantify it. I pull Allie Brosh’s webcomic on pain scale for the nurse to laugh at: are you being mauled by a bear? A list of pills taken at different times over the past 24 hours. Calling the resident, waiting for a call back. Receiving blessing to drive ten minutes to the emergency room. Waiting, and waiting. Waiting. The CT scan. Waiting. The chest X-ray, performed for reasons never articulated. The surgical team on the trauma floor, too busy to visit us. The latte at Starbucks that burned my tongue. I wait. I wait. The ultrasound. I wait. My wife, alternately drugged and in pain and vomiting, enters into an experience of time that operates not as a blank spot in her memory, but a nebulous area from which nothing can be retrieved. Her brain is exhausted, but mine is endlessly awake, bright and anxious.

Later, when I describe this, I sketch out the shapes using the principles of narrative events. Time as a framing device: we arrive at this time, we depart at that one. Here is the ordering of medical tests, here is the progression of doctors that come to speak with us, each with their own theories. Here is the eventual decision, which will be revealed to be the correct one. Here is the transfer, the journey, the movement to another space.

We know, of course, how artificial this construction of narrative is. This is not how time is experienced—this is the mind telling the story of memory until it’s believed. When I tell the story, I may pause for some of Baxter’s stillness, some of my waiting. I may describe the expensive glossy magazine I bought that held pictures of even more expensive clothes within. My disgust at the magazine’s smooth, poreless bodies within that refused to tell the story of the body as I was experiencing it, my butt going numb in the ER chair, the EMT snapping on blue gloves before touching my wife’s skin, the endless presence of the translucent green vomit bags with the hard plastic ring to clutch at the top. Oxygen saturation at 83-90-96-99 (the last only with the slippery cannula wound behind her ears). Thick slices of cheddar cheese on the sandwich I finish, in spite of a vague feeling that I should be unable to eat. But these details, too, eventually become framing posts. Pauses in the hallway to mark the progress I’m taking. Again, it becomes the story of a story, a memory that builds order out of fear and anxious watching.

Here is what I remember from those hours: the idea that I needed to hold past and present and future together in my mind. I might be helpless in the passage of time, but I needed to hold the future. Conceptualizing what might happen as important as what was happening.

I think about Choose Your Own Adventure books, where the wrong flip to page 32 would guarantee your death. I was an anxious child who kept one finger hooked on the previous page. I knew, vaguely, that this was cheating. I also did not care. These books provided reassurance that life did not.

This is what Borges understood in “The Garden of Forking Paths;” all possibilities are equally likely, and we have an infinite number of choices before us. I think about Borges while I wait. I imagine different futures. One in which this was proven to be nothing; one in which it was an infection; one in which it was an obstruction; one that required immediate surgery; one that indicated cancer. Even the impossible future, the one in which everything continues to go more and more wrong, and I am ushered out of the waiting room, to wait to become or not become bereft, is present. If I believe in the theory of many worlds, all these things do happen. Somewhere, I am broken; somewhere, I do not write this because this did not happen at all; somewhere I am not married to my wife; somewhere I do not write at all. Somewhere I am no longer.

These did not happen. My wife went home, eventually. The crisis eased. But the possibilities remain. Waiting is constructed not only by beginning and end, but what each of those could be. I fantasize about things breaking in the way that they do on television, when the action on screen suddenly is suspended and then rewinds. Players rotate back to their starting positions. Broken objects reassemble themselves. Relationships are repaired. Maybe it’s simply anxiety: if I imagine the worst, fate will not see fit to surprise me with it (she’s already done that, things can work out now). It’s the worst kind of magical thinking, because I suffer for it. These imaginings are, in their own way, as real as what occurs.

Time passes. Choices are made, or made for us, by the body. Even if I write this story as a Choose Your Own Adventure or its literary, hypertextual alternative, I am still limited by the body, by my ability to write and choose, by how many infinite alternatives I can conceptualize, by how many times a reader can make a choice. But the ghosts of those choices haunt every story. They inform the decisions that we do make, those things that we did not write but that we imagined. Those traces can surface in a narrative, sometimes in an errant thought in a character’s consciousness, or as a potent description that hints at a possibility. They can nod to the glorious untidiness of our minds. If and might and could, all those conditionals, remind us of how perception and imagination are sometimes inseparable, and that what might have happened is as potent as what did.

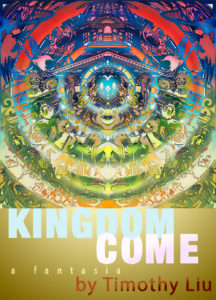

Today we are pleased to feature author Timothy Liu as our Authors Talk series contributor. In his podcast, Timothy is interviewed by Karthik Purushothaman, one of his graduate students, about his newest book,

Today we are pleased to feature author Timothy Liu as our Authors Talk series contributor. In his podcast, Timothy is interviewed by Karthik Purushothaman, one of his graduate students, about his newest book,  The pair discusses the book as a hybrid novel, and they explore the way it blends poetry and prose. Timothy also shares his process for this novel and reveals how he completed the first draft in 2008 after writing every day for three months. Karthik then asks Timothy about his inspirations, and Timothy talks about the different books that he kept on his desk while writing and how they influenced the book.

The pair discusses the book as a hybrid novel, and they explore the way it blends poetry and prose. Timothy also shares his process for this novel and reveals how he completed the first draft in 2008 after writing every day for three months. Karthik then asks Timothy about his inspirations, and Timothy talks about the different books that he kept on his desk while writing and how they influenced the book.

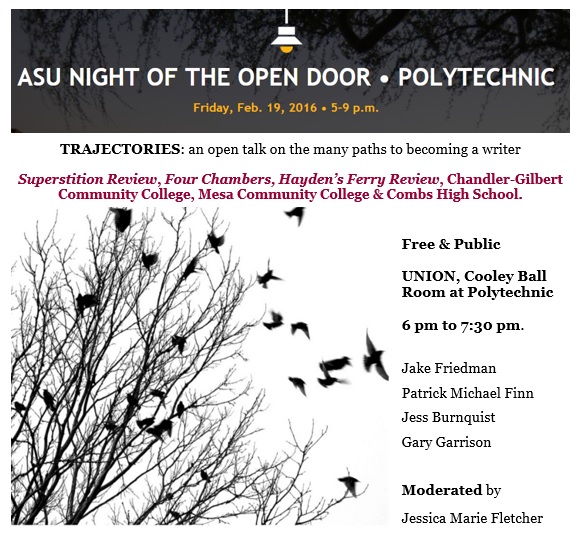

ork has appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Persona, The Washington Post, Salon, Jezebel, GOOD Magazine, Education Weekly, Time and various online journals. She is a recipient of the Joan Frazier Memorial Award for the Arts at ASU. Jess currently teaches English and Creative Writing in San Tan Valley and has been honored with a Sylvan Silver Apple Award for teaching. She resides in the greater Phoenix metropolitan area with her husband, son, and daughter. Links to her most recent work are available at

ork has appeared in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Persona, The Washington Post, Salon, Jezebel, GOOD Magazine, Education Weekly, Time and various online journals. She is a recipient of the Joan Frazier Memorial Award for the Arts at ASU. Jess currently teaches English and Creative Writing in San Tan Valley and has been honored with a Sylvan Silver Apple Award for teaching. She resides in the greater Phoenix metropolitan area with her husband, son, and daughter. Links to her most recent work are available at

n Chief of an independent community literary journal and small press based in Phoenix, AZ called Four Chambers. He is also; drinking coffee (as the picture would indicate); a waiter and sometimes bartender at an unnamed casual-upscale restaurant (the restaurant being unnamed to protect it’s identity, not actually unnamed); working on a long-form experimental prose manuscript titled The Waiter Explains (no coincidence with his current profession, he swears; long-form experimental prose being a pretentious way of saying novel, even though he has legitimate reasons for doing so involving narrative perspective and deep structure he still feels pretentious).

n Chief of an independent community literary journal and small press based in Phoenix, AZ called Four Chambers. He is also; drinking coffee (as the picture would indicate); a waiter and sometimes bartender at an unnamed casual-upscale restaurant (the restaurant being unnamed to protect it’s identity, not actually unnamed); working on a long-form experimental prose manuscript titled The Waiter Explains (no coincidence with his current profession, he swears; long-form experimental prose being a pretentious way of saying novel, even though he has legitimate reasons for doing so involving narrative perspective and deep structure he still feels pretentious).