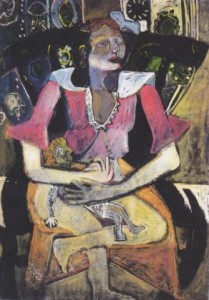

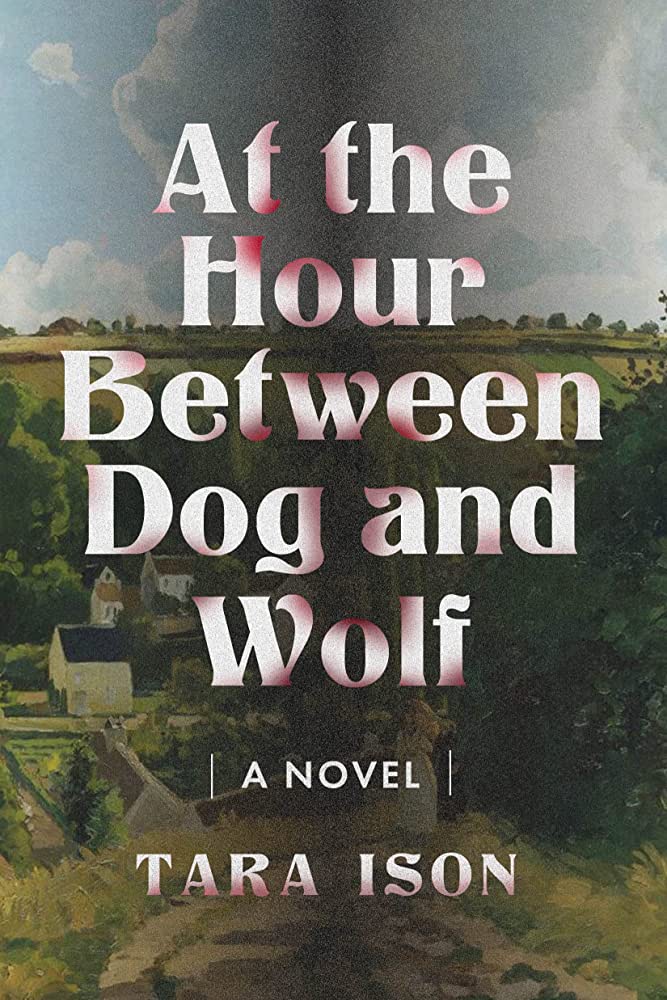

Congratulations to Tara Ison on her new novel At the Hour Between Dog and Wolf, published by Ig Publishing. Set during World War II France, the story follows Danielle, a young Jewish girl. After her father is killed, she’s forced into hiding as Marie-Jeanne, a Catholic orphan, in a small farming village. Although she only pretends to be Marie-Jeanne at first, the line between Danielle and her false identity begin to blur, even to herself: “But now the Marie-Jeanne me and the Danielle me have to be crossed over and doubled together all the time… I’d hate to get stuck this way forever, just because I blinked.”

While At the Hour Between Dog and Wolf carries considerable commentary about fascism on the global scale, the story truly shines as a slow, personal descent into what fear—and the promise of safety—can do to someone. With dazzling prose and deeply nuanced characters, Tara Ison’s novel offers both horrific tragedy and the possibility of redemption.

Told from the perspective of a young Jewish girl grappling with identity, Ison’s timely book considers that moment between dusk and night, the almost imperceptible shift into darkness, both political and personal, as it exposes the high cost of accommodation of evil and bigotry. Provocative, vivid, and affecting, this novel will inspire important conversations that we all need to be having now.

EJ Levy, author of The Cape doctor

Tara Ison is the author of The List (Scribner), A Child out of Alcatraz (Faber & Faber, Inc.), a Finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and Rockaway (Counterpoint/Soft Skull Press), featured as one of the “Best Books of Summer” in O, The Oprah Magazine, July 2013. Her essay collection, Reeling Through Life: How I Learned to Live, Love, and Die at the Movies, was the Winner of the PEN Southwest Book Award for Best Creative Nonfiction. She earned her MFA in Fiction & Literature from Bennington College and has taught creative writing at Washington University in St. Louis, Northwestern University, Ohio State University, Goddard College, Antioch University Los Angeles, and UC Riverside Palm Desert. She is currently Professor of Fiction at Arizona State University. To learn more, visit her website.

At the Hour Between Dog and Wolf is a thrilling novel, not just as a splendid read but as a deeply resonant work of art driven by the central yearning in the greatest literary narratives: the yearning for a self, for an identity, for a place in the world. Tara Ison has always been a writer I’ve ardently admired. Here she is at the height of her estimable powers.

Robert Olen Butler, Pulitzer-Prize winning author of A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain and Paris in the Dark

To purchase At the Hour Between Dog and Wolf, go here.

We’re also very excited to share an interview that dives deeper into Tara Ison’s book. This interview was conducted by our Blog Editor, Brennie Shoup. Please note that the transcript has been edited for clarity.

Brennie Shoup: Hello, everyone! I’m Brennie, one of the blog editors for Superstition Review this semester. And today, I’m going to be interviewing Tara Ison about her new book At the Hour Between Dog and Wolf, which details the life of a young Jewish girl—Danielle—during the German occupation of France. Tara is the award-winning author of a variety of books, short stories, poetry, and essays. We’re really happy that you agreed to do this interview. I’m personally very excited to see what you have to say. And is there anything you’d like to add, Tara?

Tara Ison: I just want to add—thank you, Brennie. I really appreciate you doing this, and I love Superstition Review, and we’ve been working together all semester. And you’re just an absolute joy, and you’re a gorgeous writer. This is really lovely—to be able to discuss with you. Thank you.

BS: Awesome! Thank you—I really love the book. I’m really happy that I get to know more about it, so… let’s get in. Our first question is—what was your inspiration for the central idea of the book? Specifically, the psychological transformation of Danielle from a young Jewish girl—basically telling lies to keep herself safe—to, as the cover says (or the back of the book says), a “strict Catholic, an anti-Semite, and a fervent disciple of fascism”?

TI: That’s a big arc to take a character, and that’s exactly what I was interested in—in trying to explore this story. I didn’t set out to write a political novel, although, in recent years, the theme of the rise of global anti-Semitism and fascism has become disturbingly timely. But at the time, that’s exactly what I was interested in: how do you take a vulnerable mind and… I think we’re all vulnerable—to some degree. But here is my character: she’s twelve years old. It’s World War II, and she is put in a position of… She was raised a rather privileged, sheltered little girl in Paris with her parents, and the war starts. Her father is killed. And her mother takes her down to live on a farm with a Catholic family and take on the persona—in hiding—as a Catholic orphan. And that’s an enormous amount of pressure to put on someone, especially an adolescent, I think.

Because, at that point, the sense of self and sense of one’s own identity… It’s still forming; it’s still fragile. And she’s told, explicitly, “If you make a mistake, the police are going to come kill all of us.” So we’ve got an adolescent mind—which I think is already in a state of vulnerability—but you pile on top of that the idea of what is at stake here if you make a mistake. And she does need to survive, and I think this is how it happened. I think, if you take a vulnerable mind and you manipulate them and indoctrinate them the right way—the leaning toward an idealogy that makes you feel safe, that tells you you’re going to be safe. That tells you, ultimately, that you are one of the better people in the world, better than a lot of those “other kinds” of people. I think, [that] can be extremely seductive. And Danielle, primarily out of fear, buys into that ideology—initially it’s just a game of pretend. But she does buy into that ideology and gets lost in the new identity and lost in that ideology. So, yeah, by the end of the novel, she has been transformed into a completely different person.

BS: Yeah, yeah. For sure, and I think—I don’t know—it was so tragic to read. In a really good way, in a really beautiful way. It’s tragic. I think it’s important.

And so, for our next question: What kinds of research did you do to get the details of the book accurate? Was there any research you did that you wanted to include but couldn’t figure out how?

TI: I love this question because Brennie and I are in a class together right now—that I’m teaching—called “Research-based Fiction.” And it’s a topic that I absolutely love from a craft perspective. I love research—I always joke—partly because it’s a great excuse not to be writing. But [I love research] because of what you can discover in the process. Even if you think you have a vague idea of something, as you start doing the research, if you’re open to it… If you go into research thinking, “Okay, I need to learn this one fact that I don’t know,” I think that’s a mistake. I think if you go into research being very open-minded about “I don’t know where this is going to lead me or what I’m going to discover,” you can really discover treasures that can help shape the narrative, that can help develop character. I think it gives your character a frame of reference. It gives you information on the life they live outside the limited parameters of the story that you’re telling. And I think all of that goes toward shaping and developing three-dimensional characters.

It also gives you a language—a lexicon. Because the world we live in, or the job we have, or the society, or the religion, or the hobbies, or whatever it is… Brings us into a world with a very specific sort of metaphorical lens through which to view the world. And a vocabulary. And that kind of attention to language, I think, can create a lot of texture in the prose. Because it is the character’s frame of reference and it’s the way the character thinks. But I think, very critically, it can help you avoid cliché because a character can be expressing thoughts, emotions, philosophy, feelings, whatever… in a way that’s really, really specific to the details of their own personal experience. So it keeps you away from the more generic, “war is bad” and “love conquers all.” It can really be more grounded in characters’ experience that way.

BS: Yeah, yeah, and if it’s okay, I have a quick follow-up question. So, earlier, you mentioned you were interested in the sort of psychological aspect of the book. Did you do any research into psychology, into that sort of field?

TI: Yeah, you know, I didn’t do specific reference into, you know, what we would colloquially call “brainwashing” or the sort of Stockholm syndrome of people who are basically isolated with their oppressor, and, ultimately, as a survival mechanism, begin to identify and bond with that person. I didn’t do a lot of research into that.

I did do an enormous amount of research into the experience of hidden children during World War II. And no two stories are the same. Some children were put into hiding as infants, and never knew any other family, any other life. And at the end of the war, if they were fortunate enough to have living relatives, who, at that point, wanted to take them back, that’s a certain kind of trauma for that child. A lot of it had to do with the specific circumstances: the age of the child when they went into hiding, the circumstances… Some people were put into hiding into a relatively safe, comfortable existence. Some were put into hiding where they spent four years living in a closet, and I mean that very literally. So there’s so many different stories. And it is a fictional story—I’m not telling the story of one actual person—but I really wanted to honor the experience by understanding the range of experiences and the trauma that so many children went through. And the lingering trauma that they have had to grapple with after the war.

And, of course, this is still going on: displaced people, displaced children, refugees. This is not a phenomenon that only existed in World War II; it still exists.

BS: Well, thank you for that—that’s very interesting. So for our third question: Danielle—or Marie-Jeanne (or, as I always said in my head “Mary Jean,” very Americanized), as she thinks of herself then—does something, at the end (I don’t want to spoil it) many would consider unforgivable. What made you decide to create such devastating consequences for her transformation?

TI: I love that you said that because one of my concerns when writing this novel was that it wasn’t devastating enough. That the choices she makes, and the decisions that Marie-Jeanne makes, lead to some bad things happening, but I was worried the novel wasn’t big enough. We’re mostly limited to the village where she lives. I was worried there wasn’t enough drama or enough big war stuff happening in the novel. But my instinct, again, was to make this a very internal, psychological novel. So I hope—it sounds like I hit the right balance.

Yeah, some of the decisions she makes, and the choices she makes… I think she has to face a reckoning, and I’m a believer in story pushing a character to a point of reckoning. What has happened in the story, what has befallen this character, that changes them irrevocably. And I wanted, first to Danielle, and then Marie-Jeanne, to be confronted with the consequences of some of her actions and some of her decisions in a way that would really force a reckoning, where she has to really take a look at what she has become and who she has become at the end of the novel.

BS: Well, for me as a reader, I was devastated by the end.

TI: [Laughs] It’s like again, good! I’m glad, great.

BS: Well, I think, as you mention, I could tell that it was an intentional devastation, like a good catharsis, when you see someone fall and try to get back up from that. I was very sad, but it was really good.

So, for the fourth question: The title of your novel is especially striking. As it’s explained in the book, it refers a specific time of dusk when you can’t easily distinguish dog from wolf. I love that you used it as a metaphor for basically the entire novel, but what mad you decide that it was something to focus on or include?

TI: I think… I love the title, too, I have to say. It’s long; it’s unwieldy. No one will ever be able to remember correctly. Someone searching for the book will end up, you know, “Dog books?” I stuck to my guns on the title because, as you said, I think it works on multiple levels. I came across the phrase—it’s entre chien et loup—between dog and wolf—is a French, idiomatic expression. And it means dusk or twilight. And I don’t know where—I wish I could remember what I was reading or when it happened, where I came upon that phrase, but it sort of clicked in my head.

You and I have talked about this a lot in class—metaphor can’t function as metaphor unless it first works at the literal level. It has to be organic; it has to make sense. Otherwise, you’re trying to impose poetry onto something. And it absolutely works. There’s a very literal, realistic moment early in the novel, where she and her father are walking through the streets of Paris at twilight, and he points to the sky. And [he] says, “Okay, we’re between dog and wolf at this hour, so look at the sky. And I want you to tell me the exact moment when day changes to night.” When, as you said, the dog becomes the wolf. And she’s not able to do it. There’s no exact moment you can pinpoint. And yes, I wanted that to be psychological structure of the novel—is that those tiny, tiny, tiny gradations of shading that lead my character from light to dark. I love that title, yeah, thank you.

BS: Yeah, I do, too. Once it was in the book, and knowing the premise, I was like, “Wow, this is doing so much work for the book on multiple levels.” I love it.

So, for our fifth question: Danielle’s transformation from a spoiled—or, as you said, privileged—lifestyle to a “peasant’s,” as she calls it, lifestyle is very difficult for her at first. What considerations went into depicting the different classes, or these two different class specifically, in the book?

TI: It was certainly easier, for me, to identify with Danielle’s world in the earlier days while she’s still living with her parents in Paris. Only child—I’m not an only child—but she’s an only child, rather pampered and over-privileged. She’s Jewish, but leading a secular life, as do I. Her father’s an academic. So there’s books everywhere in the house, and she develops a love of reading. So I can really relate to that twelve-year-old Danielle.

And then when she goes to live in the countryside, with, as you say, people she considers “peasants…” They’re farmers; they live in a tiny little village. They’re Catholic. She’s so disdainful of them. She thinks they’re ignorant and dirty, and their house, to her, is a hovel. She doesn’t understand how people could possibly live this way. But now she has to. And an aspect of the arc I wanted Danielle to experience was a growing appreciation for the hardness of this life. These are people who live off the land. If they don’t grow it or make it, they can’t eat, they can’t have clothes, they don’t have a house… And it’s incredibly hard work. And initially, she’s never worked a day in her life. She doesn’t know how to wash a dish.

But over the course of the story, as she bonds with this family, who have taken her in, and also as the scarcity of life in France during WWII increases… You know, very difficult to get food, very difficult to get clothing. The French had quotas of everything that had to be sent to Germans. Their milk, their vegetables, their animals, their meat… France was slowly being starved to death by the Nazi government. And Danielle has to really start working hard if she wants to eat. And she really, I think, grows to appreciate the life these people are living, and how hard they work—but also what they’ve done for her.

You know, initially, she’s so disdainful of them, but as she bonds with them, as she gets older, she wants to help take care of them the way she feels they took care of her when she was little. She doesn’t see it that way at first, but a few years down the road, she wants to take care of them. And that means taking on a lot of the responsibility of the household because these people are getting older. So, the paradox is, in a way… yes, I know she’s becoming an anti-Semitic fascist, but, in a way, she’s also becoming a better person because the values of the simple life, of hard work, of family, really start to mean something to her. Does that address the question?

BS: Yeah, I thought, even as I was reading, that it was an interesting dichotomy between how loving she was to these people. And, to be clear, I liked the family; I felt it was a very honest depiction of, of like a Catholic family, although I’m not Catholic… But I thought it was interesting that love was growing, even as her fear fueled how much she hated “the other,” as you said.

TI: It’s a complicated position for her to be in.

BS: And then… The book is from Danielle’s point of view, but you also include excerpts from her school assignments. This, to me, felt like a clever way to show readers how much she has to lie to keep herself safe, especially in the beginning. I think one of the excerpts is the beginning pages. So what gave you the idea to do this, and are these assignments based on real ones you found in your research?

TI: Um, no, no. They’re entirely invented, but they also feel perfectly normal and natural to me—that [at] the beginning of every school year, the kids are required to write a little essay. The novel is told in five sections, and a school assignment begins each section. How you’re describing it is exactly what I was hoping that they would do. Which is to act as markers for Danielle’s transformation because, in the first one, there’s the school assignment where she’s, as Marie-Jeanne, having to pretend, is talking about her wonderful life, with her uncle and aunt, who took her in, and she loves life on the farm with them. Everything is just wonderful. The assignment ends, and it immediately goes to Danielle’s voice basically saying, “This is all such a joke. This is some stupid assignment that I have to write for my new school here.” Again, she’s so disdainful of it.

So the distance between what she’s presenting in the assignment and the contrast between the real Danielle when we move into her narrative… It’s mean to be black and white in the first section. But as the sections go on, that dichotomy, that juxtaposition, becomes smaller. And in the beginnings of sections four and five, there’s no distance at all between the voice of the young woman—the teenager—writing the school assignment and who she has become. They become absolutely sincere and authentic. And I wanted to calibrate the novel, so each one of those five school assignments made really clear to the read—because they all jump forward in time a little bit—where we’re at with her transformation.

BS: Yeah, I agree. I thought that the assignments, you know, they must have been authentic. I was very much like, this feels like an assignment that a teacher would’ve given. And I think, at least for me, they do exactly that: marking her transition. And then, so this is our final question: Do you have anything you’re working on now? What’s new?

TI: [Laughs] I’m tired! I’ve been working on this novel for so long. You know, granted, I’ve done other projects, other books… I’d put Dog and Wolf down for a couple of months, maybe a couple years, but always go back to it. At this point, I’m really working on some new short stories. You know, a novel is so massive and overhwhelming, and as Henry James said (although I think I’m misquoting): “A huge, shaggy beast.” That there is something really lovely about returning to the form of the short story and being able to get my arms around it. A little bit, you know, in a different way than trying to manage the scale of the novel.

So, yeah—I’m working on some short stories, and I’ll see. I’ve got a couple of ideas for another novel, but I think it might be a little while before I’m up for it.

BS: That’s fair. I mean, I’ve never written a novel, certainly. And I struggle enough with short stories. Thank you so much, again, for agreeing to do the interview! I loved your answers.

TI: I love your questions, Brennie! This was fantastic. Thank you.

BS: Thank you. Well, it’ll go up on our blog and our YouTube page, so thank you so much!

TI: Awesome. Bye!