You have heard it all before: No one reads anymore, buys books anymore, supports small presses anymore. Fiction is taking a beating from crass consumerism and poetry has been bludgeoned to death by a stylized ennui that has no patience for long sentences like this one. Plays are either musicals or revivals of musicals. Anyone untalented can publish anything bad at any time in any format so no one has time to find the good writing. The whole culture of American literature is in one sorry state. Why should you—why should anyone—bother to write at all?

You have heard it all before: No one reads anymore, buys books anymore, supports small presses anymore. Fiction is taking a beating from crass consumerism and poetry has been bludgeoned to death by a stylized ennui that has no patience for long sentences like this one. Plays are either musicals or revivals of musicals. Anyone untalented can publish anything bad at any time in any format so no one has time to find the good writing. The whole culture of American literature is in one sorry state. Why should you—why should anyone—bother to write at all?

I am here to tell you that your poetry/short stories/essays/plays/novels—whatever your creative writing genre happens to be—matters. That your contribution to making the culture of our time matters. That your devotion to the craft of writing and your efforts to sit down and write with considered purpose and focus, or as Lucille Clifton has said, with major intent, matters.

I can say all this to you with some impunity because I have witnessed firsthand how the power of language—despite the protestations of all the cynics and the naysayers—moves audiences and readers in profound ways.

In 2012 I was nominated for U.S Professor of the Year, an awards program sponsored by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and the Council for Advancement and Support of Education (CASE). Of the award, The Chronicle of Higher Education writes: “The honor is the nation’s most prestigious teaching award.”

However, as a poet and a community college professor who teaches creative writing and women’s studies, I was certain I would never win such an award. I was certain I would not win—not because I was insecure or doubted my abilities as a poet and teacher, but precisely because I believed these abilities were at best misunderstood and, at worst, completely disregarded by most of America.

I only completed the application for the award because the very earnest and very sweet student who nominated me insisted that I do so. She sat in my office with her moon-eyes and her Tinkerbell-sweet voice insisting that I simply had to fill out the application which, as it turned out, wound up taking me 20-plus hours to complete. I simply did not have the heart to tell her no. And even as she thrust the application material into my hand, I told her yet one more time that I was not going to win. “Poets don’t win these kinds of awards, Carolyn. Please don’t be disappointed when I don’t win. I’m not going to win.”

But she was right and I was wrong. I did win.

In fact, I am the first national winner of this award that Arizona has ever had in any category. As a national winner, I was asked to give a speech at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. to an audience that included the U.S. Under Secretary of Education as well as college presidents and chancellors, deans and professors from all over the country.

Indeed, during the last few years I’ve had other successes, awards and honors, all of which have given me opportunities I would never have imagined possible when I was first starting out as a serious writer.

I have been invited to give poetry readings, speeches and workshops to audiences across the country, and I have seen the cultural cynics proved wrong many times over. As I look into the faces of strangers whose eyes seem to lock onto mine with an intensity I find both humbling and scary, I have learned—rather I have re-learned—that language used with “major intent” is still a powerful, transforming force. People tell me they are moved by my words. People tell me they have been changed. People tell me the words matter.

So, to all of you who are sitting down today to write with major intent, know that your efforts—though solitary and so often fraught with frustration, longing and despair—matter. Know that there may be one person or whole rooms of strangers who need and want to hear what you have to say. It matters to them the work you do.

It matters.

Today we are pleased to announce news about past SR contributor Irena Praitis. Irena’s newest collection of poetry, titled “

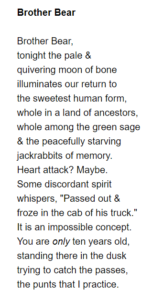

Today we are pleased to announce news about past SR contributor Irena Praitis. Irena’s newest collection of poetry, titled “ It is with a heavy heart that we here at Superstition Review would like to remember Adrian C. Louis, who passed away September 11, 2018. Louis was a two time contributor with us and we’d like to express our most heartfelt condolences to his loved ones. It was an honor to read and share his remarkable work. Here is Louis’ poem “Brother Bear,” which was published in our first issue.

It is with a heavy heart that we here at Superstition Review would like to remember Adrian C. Louis, who passed away September 11, 2018. Louis was a two time contributor with us and we’d like to express our most heartfelt condolences to his loved ones. It was an honor to read and share his remarkable work. Here is Louis’ poem “Brother Bear,” which was published in our first issue.

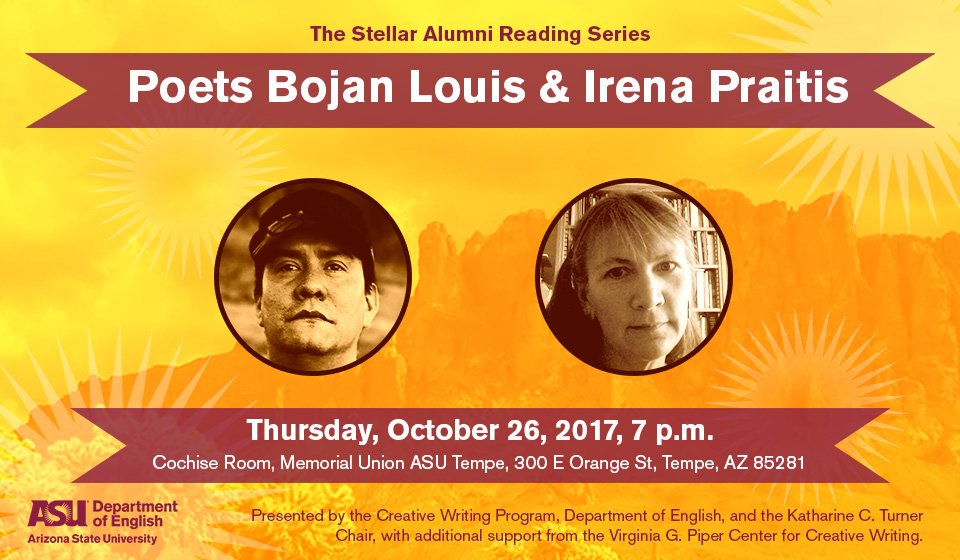

Irena Praitis will be reading from her latest book titled The Last Stone in the Circle. The collection of poetry is based on eyewitness accounts and chronicles experiences of prisoners in a WWII German work re-education camp. Purchase a copy of The Last Stone in the Circle from Small Press Distribution

Irena Praitis will be reading from her latest book titled The Last Stone in the Circle. The collection of poetry is based on eyewitness accounts and chronicles experiences of prisoners in a WWII German work re-education camp. Purchase a copy of The Last Stone in the Circle from Small Press Distribution