If I were asked to name the chief benefit of the house, I should say: the house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer…

The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard

In her 1943 essay “We Refugees” Hannah Arendt explains the predicament of the suicide that “in their own eyes” feel themselves as having failed life’s standard. Having given into despair in themselves, they die “of a kind of selfishness”; the failure of how to define, or redefine, one’s self-worth given the loss of assumed standards makes for the quandary: “If we are saved we feel humiliated, and if we are helped we feel degraded.” This quandary speaks to standards of citizenship and social belonging that in turn speak to systems of society and behavior that are radically reconfigured in the lives of displaced peoples. The refugee being a prime example of such, one that Girogio Agamben in his 2008 essay “Beyond Human Rights” argues as “perhaps the only thinkable figure for the people of our time and the only category in which one may see today… the forms and limits of a coming political community.”

I am learning of how standards are reconfigured in a year of working with Afghan families living in a school building in the center of Athens. My assumptions of dignity and belonging are changed as I am gradually invited into these lives. It begins with an invitation to have tea on the spread blankets that cover the floor of a classroom, where we leave our shoes at the blanket’s edge. Mattresses are pushed up against walls; some pillows are on the floor. I’m urged to use a pillow as I am a guest but I shake my head, saying it’s not necessary, only to realize this creates confusion and a look of disappointment, so I accept the pillow, and drink the sweetened tea. I have a bag of raisins with me. There’s a feeling of comfort and hospitality, as we drink the sweetened tea and share the raisins. We discuss the fact that some of the children are attending the Greek public school. I’m asked if I will find a dentist for a 3 year old whose top front teeth have all rotted. It will be her birthday at the end of the month. It is not the date on her paper but the one her mother gives us in April. When I’d asked her father he said he wasn’t sure what the date of her birthday was. But her mother knows, and tells me. We plan a party. I still have a string of lights with me, a cluster I’d forgotten to bring to the Christmas party we had in December. I plug them in and they start flickering, this makes Heniah, who takes a quick intake of breath, laugh. She keeps plugging and unplugging the lights as they flicker in their nest of color.

Changed circumstances will change how we see what we see. These small living spaces are made unexpectedly new. Even the city is made new. Omonia square where buses and metro stops make for intersections and gatherings, where information on squats, cell phones, fake passports, border smugglings, and plain old advice on everything from medicine to asylum petitions are hawked. It is also a world where Unés, one of the refugee children I’ve grown close to, notices things I’ve never paid attention to. He pauses in our walk along a crowded street as someone who is selling potato peelers loses his grip, and the peeler skids across the pavement, Unés picks it up, checks the blade and gives it back to the man who is surprised anyone would pick up the now broken peeler, and thanks him. We pause at a pet shop because one of the puppies catches Unés’ attention. There’s also a snake and a parrot on display. When we leave Unés points to a huge ice-cream stand with its exaggerated plastic cone. I must have seen the thing too many times to remember because it sits just outside the metro stop, but this time I see it as he does, and smile.

We speak a mix of English, Greek, and Farsi words, a jumble of emoji symbols, VIBER and WhatsApp emoticons and letters. There is salam, “hello” and bedrood, “goodbye”. Thanks to the weekly games and books and songs in English that Alicia, Judi, Eirini, Stephanie and other volunteers and donors have made generously available some of the children are now speaking in near-fluent English phrases. We have become as familiar to them as they have become to us – Rocha, Heniah, Unés, Narghes, Rakia, Azize, Maedeh – we know each other’s names, even ages. Judi is asked why she isn’t married, and if she was ever married. I’m asked if I have any children. One afternoon I show a video on my cell phone of couples dancing tango at the studio where I go. I’m asked if I do this too, Azize and her sister would like to come with me, next time I go. We go to a Luna Park where there are bumper cars and a Ferris wheel, and high-flying space-cars in which Heniah, fearless, pushes on the gears so the air-borne car will go higher. She is giddy and I am anxious. Maedeh, who is 14, comes with me to a play my daughter is in. It is Ramadan and she asks if she can skip the fast since she will be walking in the heat to the theater. Her mother is okay with this, and she dresses in white tights and her scarf and tells me you can tell the difference between Syrian and Afghan women by the way they wear their scarves. The Afghan women wear them more loosely around their heads, less tightly folded around their faces. There’s a moment in the play when the top comes off one of the actors, it’s a split-second; the actor is a statue that comes to life, her white, spray-painted breasts are bared. On our way back to the squat Maedeh will mention it, that the actor “lost her blouse” and I will nod and ask if she will tell her mother and she says she might which makes me think I may not be invited to take her daughter anywhere after this, but ask then if it surprised or bothered her. She shakes her head and says, very simply, “This is Europe.”

*

In Agamben’s essay he references Arendt’s point that one of the things the Third Reich ensured before Jews and Gypsies were sent to the extermination camps was that they had to be “fully denationalized…stripped of even that second-class citizenship to which they had been related after the Nuremberg Laws.” Agamben is making the point that the concept of the nation-state founded as it has been on assumptions of citizenship and national belonging was a way to draw the line between what lives were “doomed to death”, and which remained with human, legal, rights. He argues the point first put forward by Arendt in relation to the Jews. He notes that “What is new in our time is the growing sections of humankind are no longer representable inside the nation-state – and this novelty threatens the foundations of the later.” In other words, human rights as they have been historically tied to citizenship are now, as he explains, “Beyond Human Rights”, an insufficient insurance, or reflection, of our humanity.

I get a message from Heniah’s brother, who is 12, that her birthday party will be at 2:00, and would Judi and I like to come. Like the invitation to tea I feel it’s important to go, and want to celebrate my fearless 4 year-old’s day. I pick up a lemon pie that looks fancy and some paper plates, cups, plastic forks, party hats, and arrive after Judi. We’re invited to sit on the floor in the classroom that is now the family’s living space, the wide blankets are cleared and what was once a school desk is brought in so Heniah can sit there and blow out her candle. We’ll wait for the guests, mothers and their young children who arrive from other squats, and camps, some from as far as the Malakassa camp, where mostly Afghan families are housed; everyone arrives with a small gift, wrapped in colored paper. There are clips for Heniah’s hair, colored plastic bangles, a coloring book. There are balloons taped to the walls and the Christmas lights I’d brought are hanging from the blackboard where they have been taped. Heniah has had her hair in tiny braids so that now curls all around her face, and Rocha puts new clips into it.

But what is most impressive is the 3-layered cake that’s been prepared for the guests. My bought lemon pie, while delicious, is nothing compared to this chocolate cake, which Heniah’s mother, Azize, has made.

There is excitement as people gather. The women shed their veils and change into clothing that would make them indistinguishable from anyone else in the city. Sleeveless dresses, skirts, loose shirts with low necklines. Azize puts on make-up and earrings. When she wears lipstick I think she looks like an Italian film star, but I’m not sure which one, maybe Monica Bellucci. There is music, and then dancing; the women pull me up from the floor where I’m sitting to join them; Raikia shows me how to move my arms in a slow, sensual wave, I start to laugh, feeling awkward at first, but then happy. The children are also dancing in a circle.

Judi asks me, “who do you think is happier in a moment like this, a group of women in the UK or US or these women?” I say, without much thought, that I think right now this gathering is a very happy one, and that everyone in the room is enjoying themselves. When Judi asks Maedeh why there are no boys, or men, she says they are never present at the women’s parties but that they are not missed either. Judi asks if she wouldn’t want a boy to dance with if she liked him, and Maedeh gives an emphatic “No!” and tells us when the time comes, her father will find a boy for her and will ask her if she likes him, if not he’ll find another one. She says two boys waited for her sister who is 19; “one waited for nothing” because Mina didn’t want to go to him, and now there’s another in Sweden. Maedeh is matter-of-fact, “If a boy wants to wait and I like him then we can get married when we ready.”

We share stories, and our lives. When Maedeh speaks Judi and I expect that she and perhaps some of the other women would wish to have some of the choices we in our western worlds assume are the better ones, and find out that’s not the case, that things are also less patriarchal if more gender-specific, than what we assume. For example, Narghes, who is also 14, tells me it is her mother who will pick the wife, or suggest someone, for her older brother, because her father is dead. She tells me her father had taught her to read, and wanted her to learn languages. At some point in our conversations, I share a anecdote from Greek Orthodox weddings, that the liturgy uses the quote from the Bible about the wife fearing her husband at which point the wife stamps her husband’s foot in symbolic resistance. Azize and Maedeh look suprised, and ask why a wife would be told to be afraid of her husband, I say to remind them of who has the authority, they tell me both have, but each has a different kind.

There are other ironies and surprises; that we communicate across language and culture in ways that reinvent our language and culture. My VIBER messaging with Narghes was a mash-up of discourses, and went on from our first month of friendship. When she messaged me that she’d like a pair of black tights if I could find them for her, to when the family moved to the Malakassa camp, and finally got their papers under the family reunification law to go to Geneva. We shared hundreds of texts, emojis, voice messages, in our digital exchanges –

Bai Bai [Bye Bye] – Narghes writes, Okey [Okay]; You vato slip??? [you want to sleep???]; Hi you kam tomoro [you come tomorrow]; Andrstan [Understand]; vat taim you kam [what time you come]; Hi Adrianne you kam tomoro my mazr koking for you [you come tomorrow my mother cooking for you]; Ined nmbr hosin and maide [I need number hossein and maedeh]

*

The nation state, says Agamben is in demise, borders are being contested, people are being smuggled through at costs that sometimes include their lives, certainly the EU is in crisis, and the refugee influx has magnified what Agamben explains as the “unstoppable decline of the nation-state and general corrosion of traditional political-juridical categories.” But as Arendt said of the Jews in 1943, “Refugees driven from country to country represent the vanguard of their peoples – if they keep their identity.” These families, unhoused, as they are from country and citizenship are examples of this challenge; rather than feeling themselves as having failed life’s standard, they show us how the standard is life itself, as in sheer life, as in what it means to continue with the traditions and values that shelter us.

Narghes’ mother wants to give me a gift, it is a black patent leather bag someone has given her, and she thinks I might like it. She also ties up the bag of raisins I’ve brought because there are still some in the bag, but I say I want her to keep the raisins, and she says tashakor [thank you]. My proximity to these lives has made the obvious newly tenable, and newly proximate.

References:

Girgio Agamben, “Beyond Human Rights” Open 2008/No.15 Social Engineering http://novact.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/Beyond-Human-Rights-by-Giorgio-Agamben.pdf

Hannah Arendt, “We Refugees” in Altogether Elsewhere, Writers on Exile. Ed. Marc Robinson.

https://www-leland.stanford.edu/dept/DLCL/files/pdf/hannah_arendt_we_refugees.pdf

All photos by Adrianne Kalfopoulou

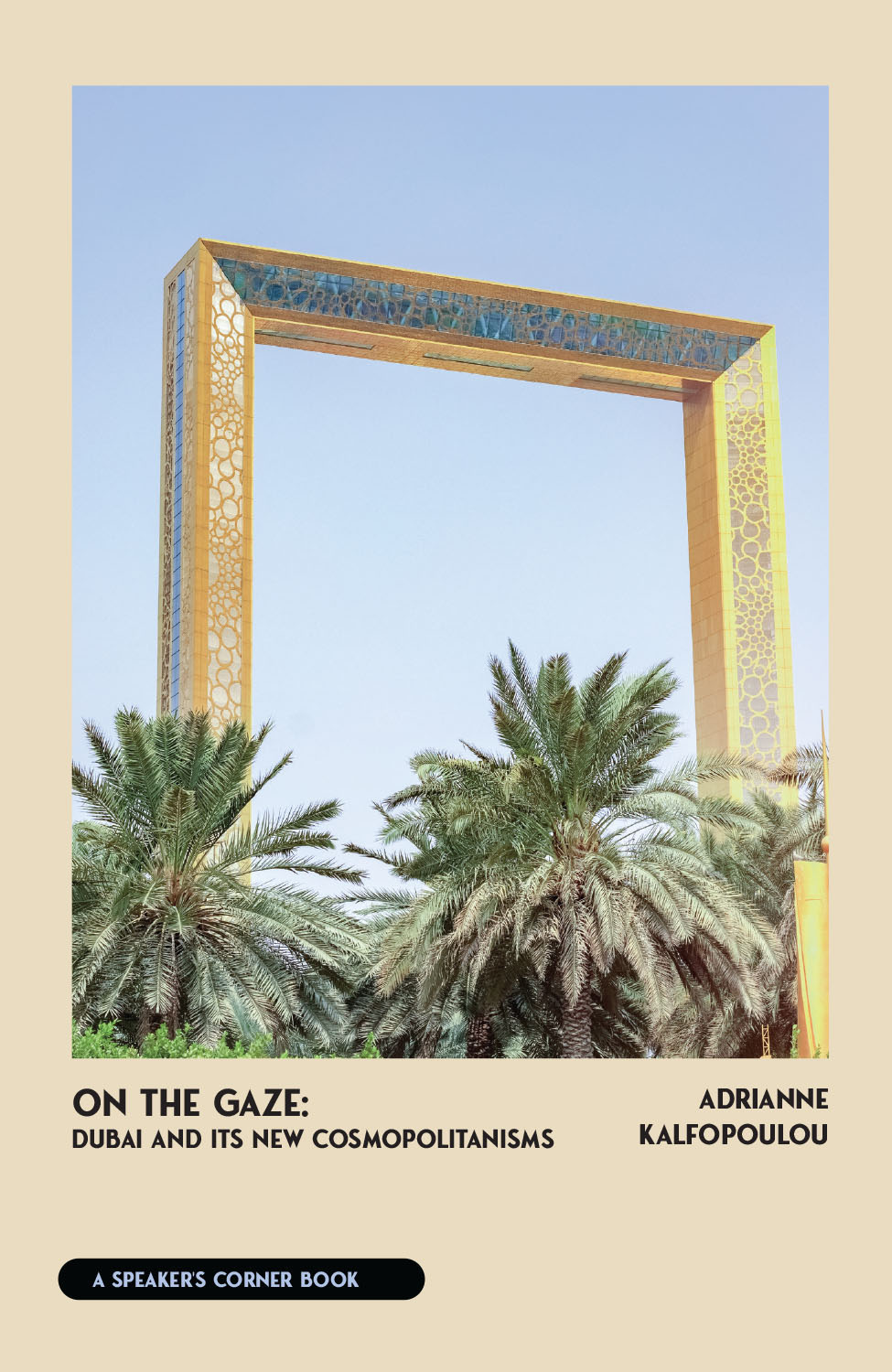

Today we are excited to announce that past contributor Adrianne Kalfopoulou has a forthcoming poetry collection titled A History of Too Much. The book is already available for

Today we are excited to announce that past contributor Adrianne Kalfopoulou has a forthcoming poetry collection titled A History of Too Much. The book is already available for  we are excited to announce that past contributor Adrianne Kalfopoulou has been recently featured in Duende, the national literary journal of Goddard College’s BFA program. Read Adrianne’s poem, “Poem in Pieces” on their website

we are excited to announce that past contributor Adrianne Kalfopoulou has been recently featured in Duende, the national literary journal of Goddard College’s BFA program. Read Adrianne’s poem, “Poem in Pieces” on their website