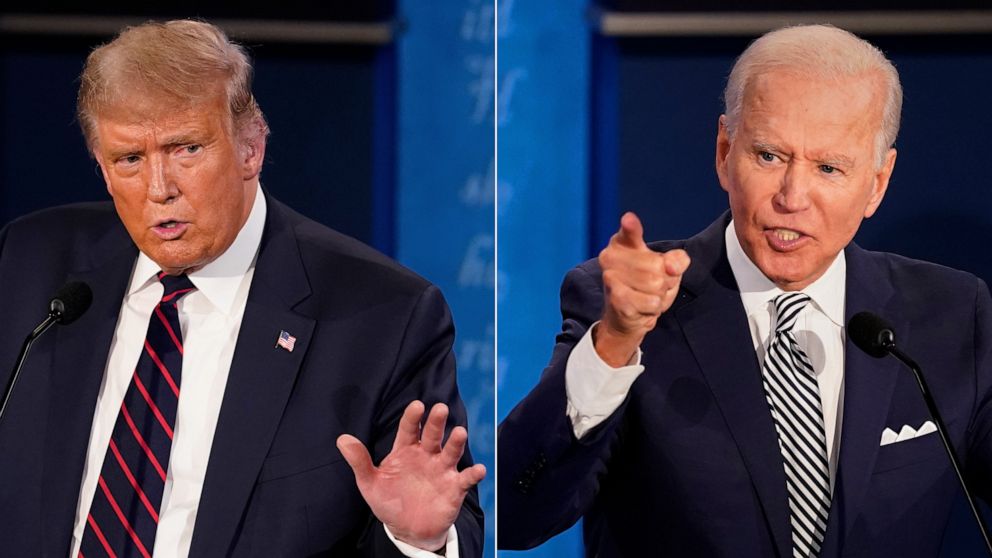

It seems so long ago now: Brexit, the British equivalent of America’s Trump moment. By a similar slight tipping of an almost equally divided electorate, that necessary legal fiction called The British People chose to leave the European Union.

It seems so long ago now: Brexit, the British equivalent of America’s Trump moment. By a similar slight tipping of an almost equally divided electorate, that necessary legal fiction called The British People chose to leave the European Union.

What the fiction concealed was a polity more split than ever, and with no wish to reconcile… not to mention the widening cracks between the four countries of the British union, the United Kingdom, or between regions of England itself.

As for the Yes/No question – making it so simple, you would think – that concealed complexities that would not have fitted on ten sides of ballot paper, let alone that one tick-box. Whichever way you voted, you’d been trying to ignore the fact that half your allies looked for all the world like enemies. Even one word, Yes or No, seemed like the answer, in each voter’s mind, to a whole array of different questions. Were you saying No, or Yes, to complicated bureaucratic legislation… or to globalisation… or to bloody foreigners… or to a gallant attempt to heal the fractiousness of a continent prone to internecine wars?

That was nine months ago – time for something, or at least some understanding, to have come to birth.

Some fifty years ago, I stumbled on the unappealing-sounding The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas Kuhn. I do care about science, but what it suggested, eye-openingly, was more. It concerned how we change. Why is it that we don’t change smoothly, incrementally, as we gain more information? Largely we don’t, not individuals any more than nations; we move in jolts and lurches, with ideas seeming to seize power in sudden coups.

Kuhn’s insight was that we live in a matrix of information, some of it fitting our current account of things, any things not. In newer terms, we think we know what is the signal, what is noise. We live with the freight of things we tell ourselves might be an error, or irrelevant, or just waiting to be better explained next week. Then one day, someone says What if that’s not the story? What if the exceptions are the story, in the margins of the page?

In Britain’s Brexit moment, we heard a blare of noise. The fact that it was being organised into a cruder, nastier and falser story is not the point. The howl of hurt unfocussed rage, of whole neighbourhoods, whole regions who saw no place for them in the current story, the yearning to uncomplicate things, violently, was going to be heard.

Was it a feeble response then, from some of us stunned by a genuine grief, to pick up our pen or laptop and write poetry? In my case, not even political poetry, not continuing the argument by other means, because my paradigm-shifting moment said: Maybe it’s the story of Yes/No that’s the problem, which we have to get beyond.

Alphabets are how young children come to language. A is for Apple, and so on. Trying to see what it was I felt such grief at losing, I found myself spelling out an alphabet of Europe, in the poem here. It contains some close-up details of European history that rarely feature in the headline stories, but that’s part of the point. Brexit barely features. The letters spelled out a wider story – of Europe already much more various than we tend to think, Europe now reeling at the impact of an age of population shift, of continents spilling, leaking great migrations. (This is not new. It’s the periods of apparent stasis that are the exceptions.) With migrant boats sinking offshore, we were struggling to be the Europe those desperate people dreamed, and we hoped, we might be. We needed to be bigger, in heart and practicality. Instead, nation by nation started backing into fear and defensiveness, into our smaller selves and stories of the way things used to be.

No, poetry is not the answer. It might look towards a better question, one that’s wider, deeper, than the Yes/No story. So few words, such a slight art form. Still, it points a way to being more.

Trying to Spell Europe

Armistice: for a minute or two, we understand each other. Silence. Then the

harder part, a life’s work: language must step in.

Banlieux: the writing in the margins of the city. Dark illumination. Yes, and we

will need to read it before we can understand ourselves.

Calais: the lost thing that inscribed itself not only on one dead queen’s heart but

thousands, where it translates into any home or hope.

Danube: not to forget, there is this other river that shapes half of Europe, that

concentrates its melancholy in the (what else?) Black Sea.

E-numbers are a way of knowing, that’s all. Of perceiving what our tongues can’t

tell. Did we think Brussels hid them, microscopic numbers in our food?

Frisian: the language most germane to English, of a country on and not on any

map, its heartland those long islands, barely more than shifting dunes.

Gross: allow me, please, this little word for Big; not just because it’s mine. Because it’s here.

Because it feels, in its bones, the swash of centuries.

Hanseatic: now, there was an empire – without borders, without army. Gabled

houses, and the weighing out of herring shoals, their scales, their silver.

Indigenous: for us, the word is affectation, scarcely old enough for habit. It’s no

time at all since the first stragglers happened on a house swept bare by ice.

John, Johann, Jean: three guys, three guises of J on our tongues, slipping from one

set of taste buds to another, as in a wine tasting: rinse, spit, taste again.

Kick out the Ks, unsettling letters. Tolerable when accompanied, as at each end of

knock. They are the crackling of boots through Northern, Eastern, forest dark.

Lulled, on the other hand, by languid sounds of Languedoc (disregard the silenced

voice in that word too) as if L was a lingua franca we could speak.

Médecins Sans Frontières, there’s a clue: not that our wounded borders are in need

of healing, but that borders are themselves the wound.

Nation: a shape that casts its shadow in the light of something other – maybe the

glare of empire; also the tiny candle of a stranger in the corner of the room.

Overseas is a word that comes too easily to islanders. Offshore (yes, with its stain

these days of dodgy dealings), that may be more to the point.

Pétanque, pelota, pesäpallo: we should give some time to other people’s games.

Not to compete, just listen to the tunk or whap against the wall next door.

Q’ran: he’s learned to write it; it disturbs him still, that letter abroad without its U,

old rules unput, and the sound of its catch in the throat.

Renaissance, Reformation, Risorgimento: it seems we never make a move without

the prefix glancing back at what was lost before.

Stars in too snug a circle on their blue-sky flag? As we know, it’s only where we’re

standing, looking, that makes any constellation hold.

Tundra crisping the Northward edges of our vision. And the South wind on the

windscreen with its gauze of desert sand. Both these define us.

Urals: there’s a skyline, and a far one, but why should this crimp in a landmass

make a continent, unless it mirrors some crimp in our minds?

Volte face or viva voce or (in acclamation) viva anything… From now, there’ll be

examinations on the border, to turn the voice back, though it only wants to live.

West is the wall we’re backed against, with, we would like to think, the setting

sun. Then it too takes ship, off, out. Leaves us standing on the shore.

X is that otherness, that and the Z, Basque shows us. As if any easy kinship was

being nixed. It’s a cross in the box, but no one tells us what the question is.

Yogh: that Saxon letter, never travelled, still leaves its guttural trace on our Y, a

shadow on each clumsy impulse towards Yes and You.

Zero, now, and zenith… Zodiac. I could go on. Wherever did you lay your hands

on words like these, their smell of spice route, alcázar, bazaar?

For the purposes of argument, let’s assume that we can distinguish between form and content in writing. The latter – content – could be taken broadly to include things like what happens in a book, who is involved in the action, and the way characters are depicted. The former – form – could be taken to include the manifold ways the story is told and shaped, along with the matters of “craft” the author brings to bear.

For the purposes of argument, let’s assume that we can distinguish between form and content in writing. The latter – content – could be taken broadly to include things like what happens in a book, who is involved in the action, and the way characters are depicted. The former – form – could be taken to include the manifold ways the story is told and shaped, along with the matters of “craft” the author brings to bear. I hover in a helicopter over a beach where my two grown sons race to catch the spy-worthy ladder I’m dangling. Once they climb up (how do those spies do it, hand-over-hand, with a fierce wind at the rungs?), my husband seals the cockpit from the poison that’s building up below, I gun the motor to leave–but to where? We hover, using up valuable fuel. Out to sea where smoke billows over the Atlantic? Up or down the nuclear-blasted north or south?

I hover in a helicopter over a beach where my two grown sons race to catch the spy-worthy ladder I’m dangling. Once they climb up (how do those spies do it, hand-over-hand, with a fierce wind at the rungs?), my husband seals the cockpit from the poison that’s building up below, I gun the motor to leave–but to where? We hover, using up valuable fuel. Out to sea where smoke billows over the Atlantic? Up or down the nuclear-blasted north or south? I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the political and the personal. When I was in graduate school, getting my MFA, my poet friends and I professed a slight scorn for poetry that was too or only or merely political. We spoke of the need for the individual voice, the lyric, the arena of mystery where a thing could not be defined by politics alone. We spoke with a what I now recognize as typical graduate school over-earnestness about how poetry had to exist in language first, as if language itself were somehow beyond or antithetical to the practice of politics. This now seems to me terribly naive, sign of a privilege we didn’t know we had. Now that I am older, and living in the America that is our America now, it seems to me, on the contrary, that everything is political, and yet the vexed crossing of the political and the personal still stands.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the political and the personal. When I was in graduate school, getting my MFA, my poet friends and I professed a slight scorn for poetry that was too or only or merely political. We spoke of the need for the individual voice, the lyric, the arena of mystery where a thing could not be defined by politics alone. We spoke with a what I now recognize as typical graduate school over-earnestness about how poetry had to exist in language first, as if language itself were somehow beyond or antithetical to the practice of politics. This now seems to me terribly naive, sign of a privilege we didn’t know we had. Now that I am older, and living in the America that is our America now, it seems to me, on the contrary, that everything is political, and yet the vexed crossing of the political and the personal still stands. It seems so long ago now: Brexit, the British equivalent of America’s Trump moment. By a similar slight tipping of an almost equally divided electorate, that necessary legal fiction called The British People chose to leave the European Union.

It seems so long ago now: Brexit, the British equivalent of America’s Trump moment. By a similar slight tipping of an almost equally divided electorate, that necessary legal fiction called The British People chose to leave the European Union.