In 2008, I lived in Australia with my family, where my wife, a pharmacologist, was on sabbatical. My daughters, then seven and twelve, attended Australian schools, and I stayed at home, completing the memoir I’d been working on since 2001.

While I was there, I took photos, captioned them for friends, and posted them as a private album on Google Picasa. At the same time, I kept a notebook in my shirt pocket, where I wrote down things I saw and ideas as they occurred to me. This blog post draws on the journal and the online album.

It seems as tiny as a snow globe now, a hemisphere peopled by the Wiggles, Peter Garrett, and a kangaroo, and paved with brick-red Outback pebbles. Its air viscous and unbreathable, as with any imagined place. Though what I imagined seems as distant to me now, as Australia itself seemed to me then.

In the weeks before we came, I did little to defray my ignorance. We were busy getting ready to leave our house and country for a year. We said goodbye to friends and then said goodbye again, when we ran into them downtown. We threw a big party and I played guitar with my neighbor Dan. Friends came from Portland; Matt brought his dobro, I set it on my lap for a few rounds of Look at Miss Ohio, and though I rarely play lap slide, the notes all fell into place. That is the nostalgic version of home: where everything is easier, and where friends show up at your house with casseroles and salads to send you off.

We switched the utilities, acquired e-mail addresses we could use overseas. I emptied bookshelves into boxes and put the boxes in the closet. I gathered every last scrap of paper I might need for the book I was writing. We backed up data and stored the disks with friends. We made copies of passports, social security numbers, immunization records. It was the final stages of the grand engineering project that had begun months before, in which a vast river of data was dammed and diverted south. Australia is, for Americans who think about it and know where it is, a kind of raw frontier: the unwelcoming Outback of Mad Max. But for us, the virtual preceded the actual. Pixels, passwords, passports. Visas and VISA.

We switched the utilities, acquired e-mail addresses we could use overseas. I emptied bookshelves into boxes and put the boxes in the closet. I gathered every last scrap of paper I might need for the book I was writing. We backed up data and stored the disks with friends. We made copies of passports, social security numbers, immunization records. It was the final stages of the grand engineering project that had begun months before, in which a vast river of data was dammed and diverted south. Australia is, for Americans who think about it and know where it is, a kind of raw frontier: the unwelcoming Outback of Mad Max. But for us, the virtual preceded the actual. Pixels, passwords, passports. Visas and VISA.

I bought a digital bathroom scale and began to weigh our luggage. We were flying on Virgin Blue, a domestic carrier, from Sydney to Melbourne, and their checked luggage allowance was less than fifty pounds per person. When you are moving somewhere for a year, less than fifty pounds a person is not much. People with more foresight send entire containers on boats. I did the next best thing: I weighed each of our bags, using myself as a human tare. Then I measured the bags’ outer dimensions. Then I made a chart, noting the ratio of Weight to Volume. It felt like a productive activity, but in the end, we chose a mix of backpacks, rolling bags, and duffles, because we would be navigating five different airports in two countries with two children, and we wanted to be able to carry everything.

What did we know about Australia? Not much. It was e-mails from friends of friends, e-mails from school administrators, estate agents, the scientist whose lab my wife would be working in. As for the neighborhood, we had the aerial view of Google Earth. We zoomed in on grainy photographs of the grid. It seemed suburban enough to have pools, but denser, mixed with retail and apartment buildings. I studied the tram map, its thick numbered lines like the nerves of a simple animal. I hoped the apartment would be quiet.

What did we know about Australia? Not much. It was e-mails from friends of friends, e-mails from school administrators, estate agents, the scientist whose lab my wife would be working in. As for the neighborhood, we had the aerial view of Google Earth. We zoomed in on grainy photographs of the grid. It seemed suburban enough to have pools, but denser, mixed with retail and apartment buildings. I studied the tram map, its thick numbered lines like the nerves of a simple animal. I hoped the apartment would be quiet.

I decided, at the last minute, to leave the waders and boots at home. I didn’t want dried-on Oregon mud to hold us up at Customs: Australia, though vast, is still an island, with an island’s vulnerability to living pests.

The fact loomed, unreal: we were moving to Australia. I imagined red dirt and kangaroos, though even “kangaroo” was a vague picture in my mind. My mother had warned me that the red kangaroos were dangerous. She had heard this somewhere, and over the years the rumor had crystallized into belief, until “red kangaroo” became synonymous with a creature whose powers of hoppity locomotion were matched only by its taste for human flesh. Presumably the Eastern Grey was friendly.

The fact loomed, unreal: we were moving to Australia. I imagined red dirt and kangaroos, though even “kangaroo” was a vague picture in my mind. My mother had warned me that the red kangaroos were dangerous. She had heard this somewhere, and over the years the rumor had crystallized into belief, until “red kangaroo” became synonymous with a creature whose powers of hoppity locomotion were matched only by its taste for human flesh. Presumably the Eastern Grey was friendly.

Having since seen kangaroos in the wild–if campgrounds, golf courses, and the Lassiter Highway count as “wild”–I’ve at least replaced the mind-cartoon I had with a living sketch. On the road to Uluru, in the desert west of Alice Springs, we saw red kangaroos that had been creamed by road trains, and lay by the roadside in varying stages of decay, from Just Napping to Bones Picked Clean. Now and then an eagle or crow rose up from the remains.

*

January. I begin buying things in the supermarket, just to take pictures of them. This goes on all year.

I narrate it the way you narrate a dream. I was in my old house, except it wasn’t my house. I ate in a Burger King, but it was called a Hungry Jack’s. They were speaking English, but it wasn’t American. Australia was not a country where everything seemed different. It was a country which was jarringly the same, and yet whose sameness broke apart everywhere you looked.

I narrate it the way you narrate a dream. I was in my old house, except it wasn’t my house. I ate in a Burger King, but it was called a Hungry Jack’s. They were speaking English, but it wasn’t American. Australia was not a country where everything seemed different. It was a country which was jarringly the same, and yet whose sameness broke apart everywhere you looked.

And yet this is wrong. It won’t do to say that Australia is like America, except–to note, for instance, the torqued vowels of ordinary Australian speech, the cleanly un-American fonts giving distances in meters (library, 200m; car park, 300m), or the egg-shaped object of Australian rules football, which looks like a regular football, but

And yet this is wrong. It won’t do to say that Australia is like America, except–to note, for instance, the torqued vowels of ordinary Australian speech, the cleanly un-American fonts giving distances in meters (library, 200m; car park, 300m), or the egg-shaped object of Australian rules football, which looks like a regular football, but  squashed at both ends. Comparison is inevitable; comparison distorts. The traveler’s reflexive habit of mind–to posit home as normative, away as variation–does not conform to the facts. Beneath the superficial perception of every surface–the supermarket cereal aisle alone, from Rice Bubbles to Sultana Bran, has undergone a sea change–is something more definite and ungraspable, like a scent: the understanding that all your life until now, you have lived in American airspace and breathed in American air, and the place you’ve moved to–Melbourne, Australia, a city of nearly four million faces, every one unfamiliar–has nothing to do with you.

squashed at both ends. Comparison is inevitable; comparison distorts. The traveler’s reflexive habit of mind–to posit home as normative, away as variation–does not conform to the facts. Beneath the superficial perception of every surface–the supermarket cereal aisle alone, from Rice Bubbles to Sultana Bran, has undergone a sea change–is something more definite and ungraspable, like a scent: the understanding that all your life until now, you have lived in American airspace and breathed in American air, and the place you’ve moved to–Melbourne, Australia, a city of nearly four million faces, every one unfamiliar–has nothing to do with you.

*

February. Just after I took this photo, we saw Cate Blanchett and her husband walking down the sidewalk, holding hands. They were smiling and chatting, and no one bothered them. They seemed to occupy a perfect, effortless force field of privacy and consideration.

February. Just after I took this photo, we saw Cate Blanchett and her husband walking down the sidewalk, holding hands. They were smiling and chatting, and no one bothered them. They seemed to occupy a perfect, effortless force field of privacy and consideration.

I remember it was a shock to see her existing in a particular place, at a particular time. As if her normal state were an immaterial Star Trek shimmer of transport, and she had condensed into existence from the ubiquity of images.

*

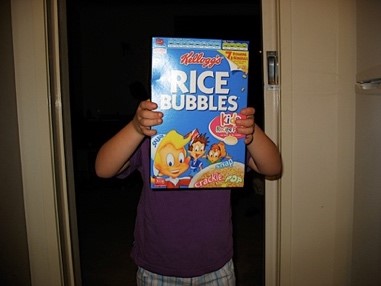

I saw this cigarette packet, with its blunt, Australian warning, lying on the tram tracks. I was in Port Melbourne, delivering Laura’s forgotten lunch to her school. At home, in Corvallis, Oregon, the one-way trip to Laura’s school is either a carbon-neutral fifteen minute walk, or a guilty three-minute drive. A forgotten lunch does not alter the day. In Australia, since we had no car, and since Laura’s school was on the other side of the city, the trip took about thirty or forty minutes, depending on the trains and trams.

I saw this cigarette packet, with its blunt, Australian warning, lying on the tram tracks. I was in Port Melbourne, delivering Laura’s forgotten lunch to her school. At home, in Corvallis, Oregon, the one-way trip to Laura’s school is either a carbon-neutral fifteen minute walk, or a guilty three-minute drive. A forgotten lunch does not alter the day. In Australia, since we had no car, and since Laura’s school was on the other side of the city, the trip took about thirty or forty minutes, depending on the trains and trams.

I’d been annoyed about having to make the trip. I was annoyed a lot in those days, annoyed to enraged. I woke up angry about nothing, or about something that was clearly irrational, a cover for something else. I write it in the past tense, though it is always a possibility, as if I were addicted to being angry. It puzzled my wife and kids and upset them. Still, I took the lunch, though I was ticking off the lost minutes on some sort of mental calculator: could’ve finished a paragraph, could’ve finished the chapter. As if the time wouldn’t have dissipated into e-mail.

But by the time I got to Laura’s school, I no longer had anything to be angry about, or the anger, like a time-lapse scab, had dried up and disappeared. I felt okay, I was happy to see Laura thriving in her classroom. Port Melbourne is one of the city’s oldest neighborhoods, its quiet, empty streets lined with rowhouses, their porches decorated with ornate iron fretwork. The private mental hurricane I woke to had faded, quick as Melbourne weather, and as I crossed the empty reserve with its gums and sycamores I could hear rosellas in the trees, a sound shocking as the flash of crimson and green, the parrot’s silhouette above. It stood out like a sign, the way everything does, and what had seemed a marker of dislocation suddenly seemed to betoken possibility.

But by the time I got to Laura’s school, I no longer had anything to be angry about, or the anger, like a time-lapse scab, had dried up and disappeared. I felt okay, I was happy to see Laura thriving in her classroom. Port Melbourne is one of the city’s oldest neighborhoods, its quiet, empty streets lined with rowhouses, their porches decorated with ornate iron fretwork. The private mental hurricane I woke to had faded, quick as Melbourne weather, and as I crossed the empty reserve with its gums and sycamores I could hear rosellas in the trees, a sound shocking as the flash of crimson and green, the parrot’s silhouette above. It stood out like a sign, the way everything does, and what had seemed a marker of dislocation suddenly seemed to betoken possibility.

In Port Melbourne, on its way to the bay, the tram line separates from the street and becomes a light rail line. You can see the trams coming from a long way away. In one direction is the Bass Strait, in the other is the Central Business District. The tracks were empty, so I stood there for half a minute and looked towards the CBD. It rose but did not loom. Its knot of skyscrapers seemed distant yet close, and above them the Eureka Tower lifted its wedge of gold.

*

Often, on my way to the Melbourne Museum, I walked by the Royal Exhibition Building. Always it was different: one weekend a Bridal Expo, with a stretch Hummer parked outside. Young couples and young women with their mothers, walking towards the front doors. Another weekend it was the Taste of Melbourne festival; another, the Home and Garden Show. I thought of the place as a giant moth, diffusing faint pheromones into the air of Melbourne which only brides-to-be or foodies or devotees of tea roses could possibly detect, and who were filtered from the insectile biomass of the city, its endless crowds.

Often, on my way to the Melbourne Museum, I walked by the Royal Exhibition Building. Always it was different: one weekend a Bridal Expo, with a stretch Hummer parked outside. Young couples and young women with their mothers, walking towards the front doors. Another weekend it was the Taste of Melbourne festival; another, the Home and Garden Show. I thought of the place as a giant moth, diffusing faint pheromones into the air of Melbourne which only brides-to-be or foodies or devotees of tea roses could possibly detect, and who were filtered from the insectile biomass of the city, its endless crowds.

*

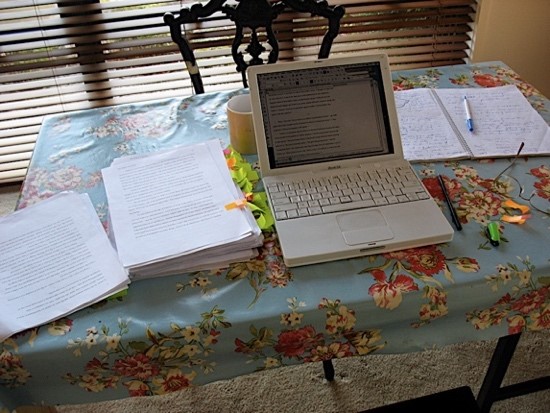

In May, I finished the memoir. This picture was taken a few days before I sent it to my then-agent; the Post-It tabs mark edits to be completed.

In May, I finished the memoir. This picture was taken a few days before I sent it to my then-agent; the Post-It tabs mark edits to be completed.

After a few weeks the rejections started to come in. Many were kind. All seemed part of a free fall, and though the tone of each was different, the uniform message was that the book—a memoir about raising my younger daughter Laura, who has Down syndrome—would not sell.

All along I had been writing a book, but as I realized — crashingly obvious, but no less true for that — a book is also a product. This was, remember, during the global financial crisis: my book was a weird investment in a time when people were already investment-shy, in a business upended not only by a cratering global economy but also by the advent of the digital.

Much later, after the book was accepted by a university press, I realized that the book’s flaws were also to blame. The story part and the history part weren’t getting along: “I keep tripping over John Langdon Down,” as my editor told me. Only then did the book begin to find its true shape. But that insight was a continent and a year away.

Much later, after the book was accepted by a university press, I realized that the book’s flaws were also to blame. The story part and the history part weren’t getting along: “I keep tripping over John Langdon Down,” as my editor told me. Only then did the book begin to find its true shape. But that insight was a continent and a year away.

I began taking pictures at night, wandering our neighborhood between laundry cycles or lagging behind the family on nights out in the CBD. I set the camera on garbage cans, retaining walls, any flat surface, slowed the exposure to an eighth or a quarter of a second, set the timer. It was a way of looking around, of registering the surfeit of detail–for that was what living in Melbourne felt like, that I was swamped with details, with crowds and signage and multistory buildings, four million layered and interwoven lives on a city that seemd an island on a country that was an island too, so that the least visual fact, the tiniest Pty Ltd or spotted-neck dove, embodied a vast displacement. The camera caught it all. It saw the things I saw, and it saw the things I didn’t see and only saw later, looking at IMG_5231 on the laptop; and this was truest of all for the photographs taken at night.

*

June 2008: Melbourne Museum

When I moved from the East Coast of the United States to the West, I moved from a deciduous world to an evergreen one. Western Oregon is defined by the Douglas fir, its scraggy greenness a discontinuous carpet in the Coast Range and the Cascade foothills. Compared to the winter-fired leaves of the northeast–an almost metallurgical glow, a blade about to be quenched–the hills outside town are monochrome. They vary with the sunlight, not the season. When you can see them through the clouds at all, or when you bother to look up.

Like other orienting assumptions I brought with me to Australia–the idea that North = Cold, for instance, or that January = Winter, or the idea that there are four seasons at all–Deciduous Versus Evergreen failed somewhere south of the equator. Australia is not Deciduous or Evergreen. Australia is Neither. Continentally speaking, it hasn’t been on speaking terms with North America since the good old days of Pangea. Australia was part of Gondwanaland, and Gondwanaland broke up, and the pieces drifted. Australia drifted north, towards the equator; it became hotter and drier, and eucalypts evolved and took over. The fern trees and southern beech forests are relics of a wetter time.

Like other orienting assumptions I brought with me to Australia–the idea that North = Cold, for instance, or that January = Winter, or the idea that there are four seasons at all–Deciduous Versus Evergreen failed somewhere south of the equator. Australia is not Deciduous or Evergreen. Australia is Neither. Continentally speaking, it hasn’t been on speaking terms with North America since the good old days of Pangea. Australia was part of Gondwanaland, and Gondwanaland broke up, and the pieces drifted. Australia drifted north, towards the equator; it became hotter and drier, and eucalypts evolved and took over. The fern trees and southern beech forests are relics of a wetter time.

So I learned on repeated visits to the Melbourne Museum, in the Forest Gallery–a soaring atrium that distills the idea of an Australian forest into examples and lessons. There are fern trees and eucalypts and beeches, most labeled. There is a burned tree with a video monitor in it, recycling a short video on bushfires. There are lizards, galaxias, turtles; there are birds, kept in by netting fifty feet above. A fairy wren, a satin bowerbird with a heap of blue scraps just beside the roped-off path.

I went to the museum often. I’d enter the Forest Gallery through the sliding glass doors, then walk up the slanted path on the left, then turn right, descending to a subterranean display: a darkened tunnel, the path illuminated by tiny lights like a landing strip or theater aisle. There was an aquarium, a waterfall, a video screen displaying both Aboriginal and Western accounts of the Yarra River’s formation.

I would emerge from the tunnel with its endlessly repeated video, its wash of recorded water and its murky fish tank, to etched metal plaques describing the relic forests. They explained how Gondwanaland divided into India, Africa, Australia, and Antarctica. The supercontinent marked with dotted lines, as if for a child’s scissors practice. In successive etchings, the continents separated and drifted, like an idea coming apart. Or a vague thought, an inkling, resolving into its divisions. That motion, that million-year drift, only one of the motions that composes the everyday: unnoticed and necessary, the planet’s rotation, the cloud systems trailed like scarves behind a dancer.

I would emerge from the tunnel with its endlessly repeated video, its wash of recorded water and its murky fish tank, to etched metal plaques describing the relic forests. They explained how Gondwanaland divided into India, Africa, Australia, and Antarctica. The supercontinent marked with dotted lines, as if for a child’s scissors practice. In successive etchings, the continents separated and drifted, like an idea coming apart. Or a vague thought, an inkling, resolving into its divisions. That motion, that million-year drift, only one of the motions that composes the everyday: unnoticed and necessary, the planet’s rotation, the cloud systems trailed like scarves behind a dancer.

*

In August, I visited Fitzroy Gardens. It’s a beautiful park, with wide, gently looping walkways and a variety of mostly native trees. But it is also the utility drawer of Melbourne parks, the place where you shove the bits of string and rubber bands and flathead screws, the things you don’t know what to do with, the parts of an unspecified machine:

(1) The actual stone cottage of Captain James Cook’s parents, disassembled, shipped across the ocean, and reassembled. It has a gift shop, and historically accurate gardens growing the things Captain Cook’s mom and dad might have grown, and a white surveillance camera mounted on a corner of the building.

(1) The actual stone cottage of Captain James Cook’s parents, disassembled, shipped across the ocean, and reassembled. It has a gift shop, and historically accurate gardens growing the things Captain Cook’s mom and dad might have grown, and a white surveillance camera mounted on a corner of the building.

(2) A plant conservatory, whose architecture echoes a Spanish mission.

(3) A Model Tudor Village, cast in concrete. The buildings reach to an average adult’s kneecap. The windows are filled in: the structures seem to be solid, all the way through. The look of the buildings (doughy, a little saggy, obviously molded from something soft) reminds one of an elaborate cake, or of a precocious child’s diorama for school.

(3) A Model Tudor Village, cast in concrete. The buildings reach to an average adult’s kneecap. The windows are filled in: the structures seem to be solid, all the way through. The look of the buildings (doughy, a little saggy, obviously molded from something soft) reminds one of an elaborate cake, or of a precocious child’s diorama for school.

(4) Miscellaneous fountains invoking river gods in which nobody, so far as I know, actually believes.

(5) A café serving light lunch fare and espresso drinks.

(6) A playground with two structures: a slide shaped like a dragon (climb up the head, slide down the tail), and two swings attached to a sort of beheaded giraffe. Reticulated, black-hooved, long-necked, but where the head should be, it has two lateral projections, like a hammerhead shark. The swings hang from the projections.

(7) A “Fairies Tree” I never could find.

In the Captain Cook house, when you ascend the steps, you hear steps ascending after you. As if the ghosts had heard you come in and wanted to join you.

In the Captain Cook house, when you ascend the steps, you hear steps ascending after you. As if the ghosts had heard you come in and wanted to join you.

Then a prerecorded conversation: Capt. Cook’s parents, Grace and James Sr., call their daughter Margaret upstairs to the fire. They talk about marrying Margaret off some day. Then Margaret is sent downstairs to bed with a candle. But before she goes to sleep – James appears! He has been serving 4 months on the Eagle and has joined the Navy!

He goes to sleep, and his father expresses hope that he may make something of himself yet. He has not yet discovered Australia.

He goes to sleep, and his father expresses hope that he may make something of himself yet. He has not yet discovered Australia.

A staginess, as if the Past knew it was past, and knew we were looking too.

Across the entrance to a room, a rope with a brass hook at each end, like a leash for a world without masters.

*

Sometimes I felt like a bowerbird. Or, more prosaically, a squirrel. I hoarded blue memories. I buried stuff in the soft ground of the brain. Now I’m digging it all up to see what it looks like.

Sometimes I felt like a bowerbird. Or, more prosaically, a squirrel. I hoarded blue memories. I buried stuff in the soft ground of the brain. Now I’m digging it all up to see what it looks like.

Some things, as if made of plastic or gold, seem utterly unchanged: a memory of a day in the Australian desert; or walking down a cramped, sunlit laneway spangled with graffiti; or the long escalator ascending from Parliament station; but others, as if organic, seem transformed by their time underground, partly or wholly decomposed, their shapes altered or changed in color or shot through with the tangles of forgetfulness; and yet others change, in an instant, when exposed to the air.

Some things, as if made of plastic or gold, seem utterly unchanged: a memory of a day in the Australian desert; or walking down a cramped, sunlit laneway spangled with graffiti; or the long escalator ascending from Parliament station; but others, as if organic, seem transformed by their time underground, partly or wholly decomposed, their shapes altered or changed in color or shot through with the tangles of forgetfulness; and yet others change, in an instant, when exposed to the air.

*

*

September. Since the memoir wasn’t getting published anytime soon, I thought I’d keep writing about Australia. I poured the continent through one topic and the next, like sieves or filters. The election. The climate. The financial crisis. But these were grand topics, and I could do little with them. What stays with me are the colors of urban Australian birds: house sparrows, their muddied browns and grays. As if painted with the water left in the jar, after one of Laura’s watercolor sessions. Pigeons: like black-and-white films poorly colorized, a filthy iridescence.

September. Since the memoir wasn’t getting published anytime soon, I thought I’d keep writing about Australia. I poured the continent through one topic and the next, like sieves or filters. The election. The climate. The financial crisis. But these were grand topics, and I could do little with them. What stays with me are the colors of urban Australian birds: house sparrows, their muddied browns and grays. As if painted with the water left in the jar, after one of Laura’s watercolor sessions. Pigeons: like black-and-white films poorly colorized, a filthy iridescence.

Once, on the platform of the South Yarra station, I saw a seagull without feet. It hopped along on its stumps, or knuckles. Its eyes impassive, or not expressive in any way I could understand.

In the Melbourne Central Food Court–a slow brown shrapnel of birds exploded above me. My wife was at work, my daughters in school. I sat with my Kurry Feast on its compartmentalized metal plate.

In the Melbourne Central Food Court–a slow brown shrapnel of birds exploded above me. My wife was at work, my daughters in school. I sat with my Kurry Feast on its compartmentalized metal plate.

In Flinders Street Station once, as we sat together eating churros, I heard furious cheeping from a couple of tables over. When I looked closer, a mob of house sparrows was tearing one of their own apart.

*

Every sense is an isotope of memory. A fragrance has a momentary half-life: each morning, when I walked out the apartment door, it was as if I’d forgotten the scent of eucalyptus while I was asleep. It was new again, or new and familiar, the way a poetic image is supposed to be. Its scent distilled the place we’d chosen, and our distance from the place we’d left behind. Now, like any decaying element, eucalyptus has become eucalyptus. I can call to mind the tootling of magpies, or the way the first-floor apartment shook as the #5 tram rumbled past, or the blue-and-yellow uniforms of the boys from the Catholic school nearby–though these memories, too, are decaying, the tootling blurred/distilled to a reedy ghostliness, the tram’s vibrations recalled but silenced, the boys’ faces erased. They are like rumors I heard from myself: uncertain, but mine. But the odors might as well be something I read about: they are utterly transformed, inert, stabilized in a word.

Every sense is an isotope of memory. A fragrance has a momentary half-life: each morning, when I walked out the apartment door, it was as if I’d forgotten the scent of eucalyptus while I was asleep. It was new again, or new and familiar, the way a poetic image is supposed to be. Its scent distilled the place we’d chosen, and our distance from the place we’d left behind. Now, like any decaying element, eucalyptus has become eucalyptus. I can call to mind the tootling of magpies, or the way the first-floor apartment shook as the #5 tram rumbled past, or the blue-and-yellow uniforms of the boys from the Catholic school nearby–though these memories, too, are decaying, the tootling blurred/distilled to a reedy ghostliness, the tram’s vibrations recalled but silenced, the boys’ faces erased. They are like rumors I heard from myself: uncertain, but mine. But the odors might as well be something I read about: they are utterly transformed, inert, stabilized in a word.

One morning in the Australian spring, walking out of the apartment as always to wait for Laura’s bus to whip out and angle across commuter traffic, I noticed the scent of eucalyptus, and realized I had lived in Australia long enough to have that scent numbed by cold and reawakened. I inhaled the spring, the way I did as a suburban child, except it was September, and I was forty-three, and the spring smelled newly strange.

One morning in the Australian spring, walking out of the apartment as always to wait for Laura’s bus to whip out and angle across commuter traffic, I noticed the scent of eucalyptus, and realized I had lived in Australia long enough to have that scent numbed by cold and reawakened. I inhaled the spring, the way I did as a suburban child, except it was September, and I was forty-three, and the spring smelled newly strange.

If could I conjure that sense, unscrew the sealed jar of Australian air I carry in my brain, measure its parts per million, I would find the pure astringent strains of eucalyptus admixed with car exhaust, loam, artificial grass, cigarette smoke, dry cleaning chemicals, a musty box of clothes and toys dumped on the doorstep of the Op Shop, and a few molecules drifting over from the bakeries and butchers on Glenferrie Road.

In this model, I am the constant, the observer, the Geiger counter, and my memories of Australia are what fade. In truth, it is Australia that endures, and I am decaying; and long after the last atom of what I am has broken down, been reabsorbed, raised like ash or as ash into the weather patterns I have done my part to change, Australia will renew itself, and will smell pretty much the same, in its September spring.

*

Wandering through the Immigration Museum, I saw a late 19th century lithograph of a crowded Melbourne wharf. It was like a child’s drawing, the perfect triangles of rigging bisected by masts. I imagine them as the triangles that wrap Federation Square now, a tessellation of the past.

Wandering through the Immigration Museum, I saw a late 19th century lithograph of a crowded Melbourne wharf. It was like a child’s drawing, the perfect triangles of rigging bisected by masts. I imagine them as the triangles that wrap Federation Square now, a tessellation of the past.

The wharves were crowded because gold had been discovered. In time the river of gold dwindled, and the speculative real estate bubble eventually popped. As a friend told me, that’s why, when you walk up Glenferrie Road, the dates on  the second story of each building–formed in concrete like foundation stones in the air–stop at 1890. For over a decade the depression brought new building to a halt.

the second story of each building–formed in concrete like foundation stones in the air–stop at 1890. For over a decade the depression brought new building to a halt.

A bubble. I imagine the gold beaten to a thin tissue and inflated. Then bursting, leaving a residue of houses and railroads and buildings.

*

November.

*

Things temporary residents do that tourists don’t: Pay utility bills. Chaperone on school field trips. Visit tiny, local parks multiple times. Begin to recognize faces on the street. Begin to be recognized. Buy furniture. Rent an apartment.

Longer term than us: Acquire accents. Acquire citizenship. Stay.

*

Fragments from the shirt pocket journal, November:

Fragments from the shirt pocket journal, November:

Living here, I think of the convenience of the Bionic Woman’s adventures, which always featured a distant conversation she could use her Bionic Ear to listen to, just as the Six Million Dollar Man was called upon to spy on faraway objects with his Bionic Eye.

If only life furnished events so precisely calibrated to our talents. This is what we are doing with our jobs, our careers, our lives, to increase the probability of this convergence.

Moving to Australia was the opposite of this. We moved here because we could. It was more difficult–we knew how to be ourselves in Oregon–but it has been worth it, if only to prove to ourselves that at this late date, we can alter our talents to fit the surroundings.

*

Sadistically bad tram driver. His lurching would produce motion sickness in a rock.

Two seats ahead of me, a woman with her mirrored compact hinged open, as if taking a bearing on a distant mountain.

Touch screen display in the National Gallery of Victoria, in The Cricket & the Dragon: Animals in Asian Art:

You are energetic, excitable, and stubborn.

The dragon rules the hours

7 a.m.

to

9 a.m.

because this is when dragons begin to produce rain.

December. I sat–I was going to say, in the shadow of the Shot Tower, but the tower is enclosed by a shopping mall, and malls, for the most part, are free of shadow. Their light is atrial, diffuse. It is not meant to be noticed. But if you were to look up, you’d find, mingled with neon and incandescence and fluorescence, an actual daylight filtering down from the Antipodean sky; and looking up, one would see the Shot Tower, a brick tower like a smokestack without a factory, enclosed beneath a cone of gridded glass.

December. I sat–I was going to say, in the shadow of the Shot Tower, but the tower is enclosed by a shopping mall, and malls, for the most part, are free of shadow. Their light is atrial, diffuse. It is not meant to be noticed. But if you were to look up, you’d find, mingled with neon and incandescence and fluorescence, an actual daylight filtering down from the Antipodean sky; and looking up, one would see the Shot Tower, a brick tower like a smokestack without a factory, enclosed beneath a cone of gridded glass.

Buckets of molten lead were hauled up to the top of the tower, then poured through a sort of colander. As the streams of lead fell through the air, they separated into teardrops, which solidified into spheres. A huge basin of water waited at the bottom, to cool the shot. It seemed like writing to me, the transformations involved: memory mined, refined, melted down, and winched up–molten, poisonous, heavy, formless–to be turned into something useful. A weapon, something to sell.

I like the idea of something taking form as it falls, and its form becoming permanent from the way it lands.

In the runup to Christmas, a gigantic implied Christmas tree, made from golden spheres—a Ferrero Rocher promotion—was hung beside the shot tower, as if some alchemy had transmuted lead shot into gold.

In the runup to Christmas, a gigantic implied Christmas tree, made from golden spheres—a Ferrero Rocher promotion—was hung beside the shot tower, as if some alchemy had transmuted lead shot into gold.

The Shot Tower is a museum now. You enter through the R.M. Williams store, past sales displays which–even to my American eyes, and even adjusting for the exchange rate, the cachet of the brand, and the general priciness of Melbourne–did not compute as bargains: a pair of shorts and T-shirt for only $100! Like everything else, R.M. Williams seemed underwater-familiar, mixing things I understood fluently (casual sportswear, shopping with credit cards, the idea of the frontier) with things unfamiliar (horse-related objects, the mystique of R.M. Williams, the Australian frontier). Tim Flannery, the Australian scientist, writes in his memoir that getting outfitted at R.M. Williams was a rite of passage for young Australian men.

*

Undated journal entry:

We are shrinking America. It is all we knew until we got here, it was our oxygen and our ground, and its shores were our shores. But the gift of distance is to know that this mindset is an island.

Sometimes I feel as if I am reclining in a soft planetarium seat, looking up at a field of white dots, and a helpful baritone voice is explaining the strange constellations, the ones I have never seen, and highlighting them with lines of force. These three dots are The Playground. These are The Lamington. These are The Wallaby, The Platypus, The Tram.

They are the lights, the pattern, but they appear against the dark: thick, velvety with the buzzing the eye makes to fill an absence. A depression, an artificial dark, the unlit interior of a hemisphere. I’m that dark, and the mysterious projector too, all brushed metal and pierced with light and pivoting to alter the display; and I’m the voice in the room that sounds like mine, and the one half-dozing in the chair, who startles when the lights come up.